Chapter Two: Mud is US

If you spend much time squelching through  Oregon’s soggy landscapes you might get the feeling that we have only recently squeezed from the primordial mud. And that might not be too far off, if you permit me to readjust your watch to count eons instead of minutes.

Oregon’s soggy landscapes you might get the feeling that we have only recently squeezed from the primordial mud. And that might not be too far off, if you permit me to readjust your watch to count eons instead of minutes.

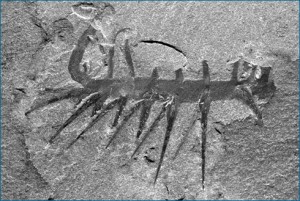

Trilobytes galore

Less than a complete eon ago, just a mere 400 million years ago, during the Oligocene period Idaho had a lock on the best tropical beachfront property in the Northwest, but demand was a bit sluggish since only a few ungainly amphibians had actually waddled ashore to discover the benefits of terra firma. Instead the real action was in Oregon, which was covered by a subtropical sea and dotted with corral reefs. These warm waters were teaming with whimsical life forms. Jellyfish floated aimlessly in the waters, worms squirmed through the silted seabed, centipedes marched stoically across the muddy ocean floors and trilobites sporting fancy ribbed carapaces dominated the social scene for more than 350 million years. But as our emerging continent migrated slowly northwards cooling water temperatures would soon introduce new species like starfish, cuttlefish, bi-valve clams, horseshoe crabs, sharks and primitive vegetation on land.

In the meantime, the mud that I mentioned earlier was continuing to flow unabated into the shallow sea covering the eon’s worth of discarded trilobite carapaces, the remains of the myriad centipedes and the near infinite squiggly-wigglies that perished in that tepid bath that covered our present-day Oregon. Baked into the primordial muck for eternity these caked layers sank quietly into the earth’s crust. But here and there the stresses and jostling of the earth’s skin would force one of these long-buried layers to the surface to reveal a crowded catacomb of early protean life.

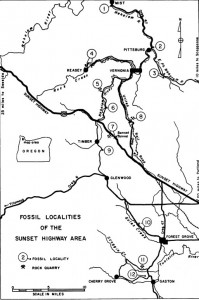

For those with the feet to discover these troves and the eyes to discern them, many of the North Coast mountains’ moss-covered outcroppings serve as remarkable windows into an antiquity beyond comprehension to most of us. The vicinities of the Sunset Highway are rich in paleontological evidence of this long-ago era in which mud itself was both the stimulus for life and the coffin to which it was confined once the shallow seas in Oregon dried to become the basis for our current muddy existence.

That said, my best find was not a crumbling mollusk, but rather an old report issued by the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries (DOGAMI) in 1957 and written by Margaret L. Steere. With that pragmatic certainty that characterized so our post-war years, Margaret begins her report with the incontrovertible assertion that “the Sunset Highway area…is famous for its abundant marine fossils of the Oligocene Age.” Why, of course, silly me for not immediately knowing that!

That said, my best find was not a crumbling mollusk, but rather an old report issued by the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries (DOGAMI) in 1957 and written by Margaret L. Steere. With that pragmatic certainty that characterized so our post-war years, Margaret begins her report with the incontrovertible assertion that “the Sunset Highway area…is famous for its abundant marine fossils of the Oligocene Age.” Why, of course, silly me for not immediately knowing that!

So what is the history of this region? Maybe to best way to begin that examination is to look at our filthy boots. Sticking to the soles of those boots is a yellow-brown clay commonly referred to as Portland Hills Silt that was deposited here during the last ice-age, about 14,000 years ago. But just below that we find the final chapters of a long drama that raged across this landscape.

Wall-to-wall basalt followed by a gentle wash of flotsam and jetsam.

It all began in a distant time before the Cascade Mountains arose and basalt lava was welling up like molten wax across the land scape from Eastern Oregon all the way to the Pacific. When these “flood basalts” flowed into the Portland area more than 16 million years ago they even temporarily blocked the Columbia River, diverting it via Salem and forcing it into the Pacific near Lincoln City. Repeated floods of molten basalt rock continued to inundate the region, with each layer being eroded by time and reduced to clay. The red crust frequently encountered on exposed basalt in the Tualatin Mountains dates back to a time when our area enjoyed a tropical climate. Then about eight million years ago the tectonic forces that pushed up the North Cascades also folded these basaltic flows into the Tualatin Mountains, the Coastal Range and the present coast line.

During this period and extending as recently as two million years ago successive waves of waterborne sediment known as the Troutdale Formation washed up against the base of the Tualatin Hills depositing quartzite, schists and granites scoured from the bed of the Columbia River, as well as sandstone eroded from the Cascades.

Towards the end of this period, only a few hundred thousand years ago, volcanoes began to erupt across the lower Willamette Valley. Most of the taller isolated hills in Portland derive from this period. Referred to as the Boring Volcanoes, they produced basaltic lava that can easily be distinguished from Columbia River Basalt by its gray color. Look for this it along the ridge tops and west slopes of the Tualatin Mountains.

The 32 Boring volcanoes in the Portland area had barely cooled when our ancestors arrived on the scene some 13,00 to 15,000 years ago – just in time to witness the horrific Missoula Floods that repeatedly burst through an ice dam in Western Montana sending 500 cubic miles of water in a gargantuan torrent across eastern Oregon and Washington. As this towering mass of water piled through the Columbia River Gorge at nearly 65 miles an hour it rose to a height of 500 feet and five miles across. The ground would have literally shaken as this cataclysmic eruption stripped away top soil, cut huge canyons into the mountain sides and literally tore away at the bedrock of the Columbia River.

Lest we think that the great cataclysmic tumult that forged this savage place has relented in the face of human endeavor, the 1981 eruption of Mount St. Helens gave ample warning that the primeval forces still rule this country. We all know that we’re in for a “big one” soon as the tectonic plates below us jockey into position for the big “snap” that will send hillsides into the valleys, drop our coastal benches into the rising sea, and do untold damage to the fragile infrastructure that keeps us alive. Look upon these lands with awe, wonder and perhaps a little trepidation for Nature is not shy about revealing its awesome power in these parts.