Brief summary: This is the final segment of the Northern Route connecting Forest Park to Seaside, Oregon. This segment consists of a long sloping descent along well maintained (exception one washed out ravine) logging roads descending from 2200 ft to Seaside over 18 miles. Tremendous views; very exhilarating.

Brief summary: This is the final segment of the Northern Route connecting Forest Park to Seaside, Oregon. This segment consists of a long sloping descent along well maintained (exception one washed out ravine) logging roads descending from 2200 ft to Seaside over 18 miles. Tremendous views; very exhilarating.Distance: 18.7 miles

Biking duration: 4 hours 30 minutes

Travel time to trail head: 90 minutes to pull off on Saddle mountain access road. Does not include additional time to position second car in Seaside.

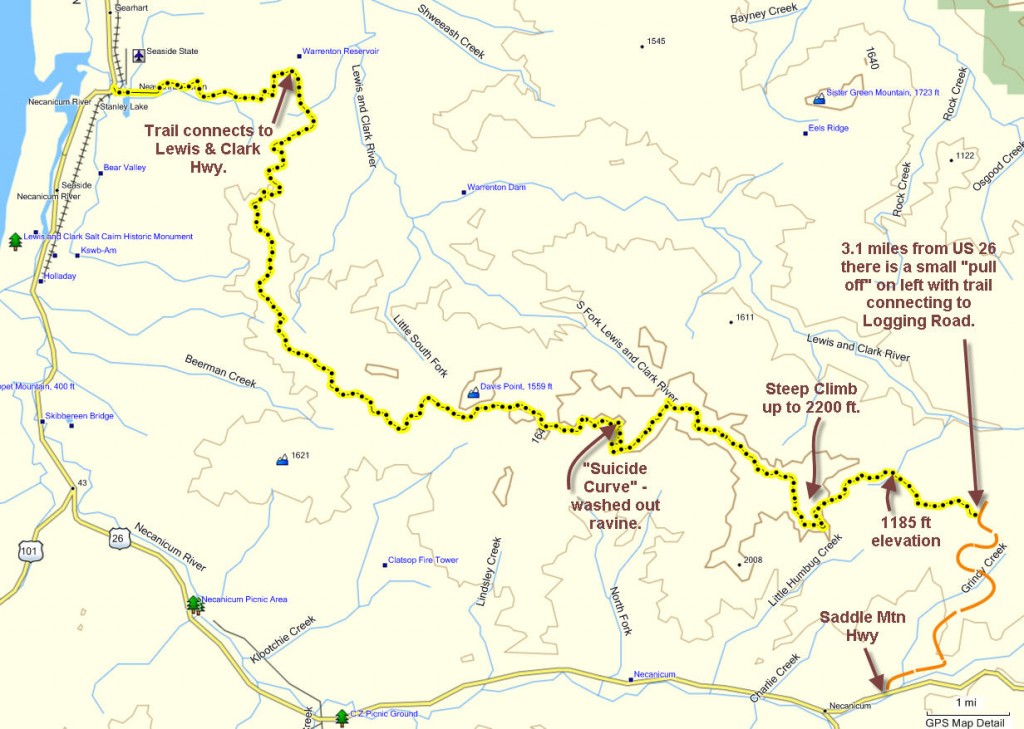

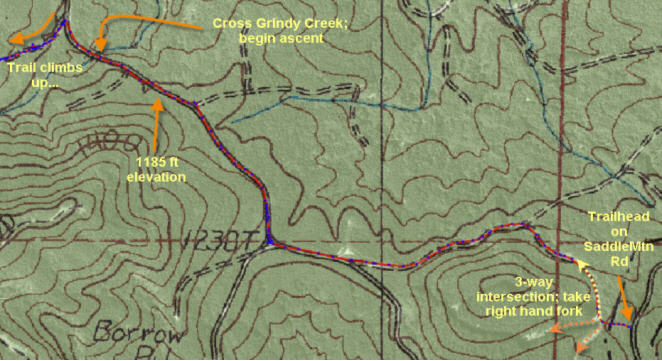

Driving directions to the trail head: From downtown Portland drive west on US 26 for 64.1 miles to the Saddle Mountain highway. Drive up the Saddle Mountain highway for 3.1 miles and pull of on the left side of the road in the slight pull-off area located there. Locate the trail leading west into the forest that leads to a 3-way intersection on a nearby logging road.

Elevation change: 947 feet from Grindy Creek to summit of Elk bugle pass – in 2.53 miles

Conditions: graveled logging roads, short distance of clear forest path, and one washed out ravine requiring a traverse down a steep stony slope

Ridge runners’ Delight covers the last 18 miles to the Coast, and what a ride it is!

When it came time to explore this last section of the trail to the coast, I had planned an overnight hike, covering the 18 to 20 miles in two days. Unfortunately, plans went awry and we had only one day to accomplish this hike. So we resolved to make the push through in one day – using bikes!

Now mind you, I’m a walker not a biker. I do own and occasionally ride a sturdy street bike with decent tires that have real tread, but I am not a season two-wheeler. And my companion James Benson was likewise bicycle challenged and ended up using his wife’s bike – a “semi” Mountain Bike with fatter tires than mine. But this was to be one of the first times we’d ventured out onto the logging roads depending upon more than our shoe leather.

Our prior hike in the long series of hikes between Portland and the Coast, had taken us from Vinemaple located on the Nehalem River up Boiler Ridge to Saddle Mountain. Following the paved Saddle Mountain Road we then traversed the north side and western shoulder of Humbug Mountain and eventually reached an area directly west of Saddle mountain on the western shoulder of Humbug Mountain. At that time we had penetrated the logging road network by bushwhacking westward off of Saddle Mountain Road until we located one of the logging roads that served that slope. On that prior trip we had  penetrated west of Saddle Mountain as far as Grindy Creek, before we resolved to finish our trip another time. From Grindy Creek we had retraced our steps back to the Saddle Mountain Road, emerging on a logging road that intersected with this paved access road half way down the mountain to US 26.

penetrated west of Saddle Mountain as far as Grindy Creek, before we resolved to finish our trip another time. From Grindy Creek we had retraced our steps back to the Saddle Mountain Road, emerging on a logging road that intersected with this paved access road half way down the mountain to US 26.

On this excursion we began by seeking out a more direct way to bushwhack into the logging road network that descended westwards

in a series of peaks down to the Neawanna Heights overlooking Seaside. Our original bushwhack into this logging network had not been as easy to follow as we might have hoped so we were pleased to find a visible short trail connecting the Saddle Mountain road to the logging roads located exactly 3.1 miles from the base of Saddle Mountain road.

Humbug Mountain access path:

Look for a wide shoulder on the left side of the road and a path leading west through the trees.  This bring you to an intersection of three logging roads at an elevation of 1365 ft. Use the right hand fork that proceeds northwards and winds downhill to the intersection with Grindy Creek. Before reaching Grindy Creek you will pass a poorly maintained side road coming in from the north (right side), and you will also pass an intersection with a well maintained road leading downwards from you left. This is the trail that we took to exit the area on our last attempt and it eventually leads back to the Saddle Mountain Road. The road passes another intersection shortly thereafter, and you should choose the right hand fork that leads uphill along the ridge that divides the watershed. On your right are streams that flow into the Lewis and Clark River eventually flowing into Young’s Bay and reaching the sea by way of Astoria. On the left are streams, like Grindy , Charlie and Klootchie Creeks that flow into the Necanicum which runs alongside US 26 and debauches into the Pacific at Seaside.

This bring you to an intersection of three logging roads at an elevation of 1365 ft. Use the right hand fork that proceeds northwards and winds downhill to the intersection with Grindy Creek. Before reaching Grindy Creek you will pass a poorly maintained side road coming in from the north (right side), and you will also pass an intersection with a well maintained road leading downwards from you left. This is the trail that we took to exit the area on our last attempt and it eventually leads back to the Saddle Mountain Road. The road passes another intersection shortly thereafter, and you should choose the right hand fork that leads uphill along the ridge that divides the watershed. On your right are streams that flow into the Lewis and Clark River eventually flowing into Young’s Bay and reaching the sea by way of Astoria. On the left are streams, like Grindy , Charlie and Klootchie Creeks that flow into the Necanicum which runs alongside US 26 and debauches into the Pacific at Seaside.

As we follow this ridge-line road it eventually crosses Grindy Creek at an elevation of 1185 feet.

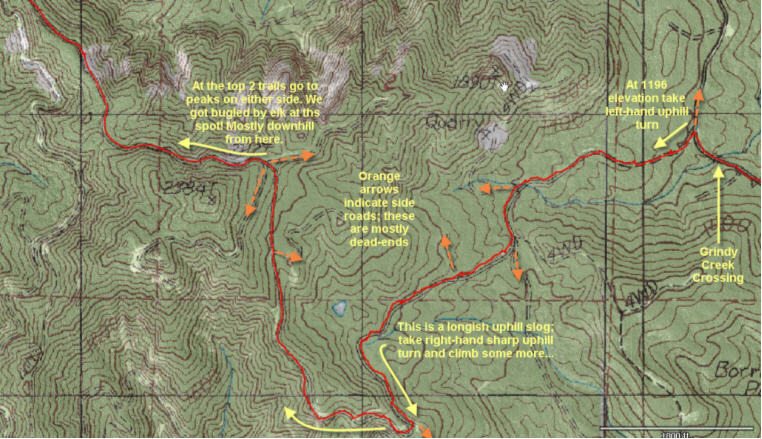

Shortly after crossing Grindy Creek, the trail splits what what appears to be the main route heading rightwards. This is an alternative route that circles around the peak directly ahead. But we, being gluttons for punishment, take the left hand fork and begin the long trudge uphill pushing our bikes, for lack of decent bike conditioning.

Shortly after crossing Grindy Creek, the trail splits what what appears to be the main route heading rightwards. This is an alternative route that circles around the peak directly ahead. But we, being gluttons for punishment, take the left hand fork and begin the long trudge uphill pushing our bikes, for lack of decent bike conditioning.  From here the trail leads upwards for what seems like an eternity before reaching the summit – at an elevation of about 2148 ft.This traverse is about 2.2 miles long and rises about 921 ft as it passes through a middle-aged alder forest, crossing 3 side trails. This road is also well used by the elk and dear as evidenced by frequent scat and continuous prints along the way. Eventually, the road turns abruptly upwards to the right, while the straight option stays level, but shows far less use. We will follow the well-trodden road up and around the end of the ridge. As we emerge from the climb the road opens up to the south affording us with the first spectacular views of the mountain south of US 26. From here the road levels out a bit rising only about 377 ft in elevation over the next mile where it crests at 2148 ft (3.43 miles from start). Just below this summit James and I were accosted by an elk bugling from a mere 50 feet away from the road. The rather nasally bugle culminated by a brief whistle coda was most impressive,

From here the trail leads upwards for what seems like an eternity before reaching the summit – at an elevation of about 2148 ft.This traverse is about 2.2 miles long and rises about 921 ft as it passes through a middle-aged alder forest, crossing 3 side trails. This road is also well used by the elk and dear as evidenced by frequent scat and continuous prints along the way. Eventually, the road turns abruptly upwards to the right, while the straight option stays level, but shows far less use. We will follow the well-trodden road up and around the end of the ridge. As we emerge from the climb the road opens up to the south affording us with the first spectacular views of the mountain south of US 26. From here the road levels out a bit rising only about 377 ft in elevation over the next mile where it crests at 2148 ft (3.43 miles from start). Just below this summit James and I were accosted by an elk bugling from a mere 50 feet away from the road. The rather nasally bugle culminated by a brief whistle coda was most impressive,  but our challenger evidently thought better about showing himself – and since the hunting season had already started might be an unwise move. Nonetheless we heard his heavy hooves on the forest floor as he made his exit. The height of land lay just ahead, so I’ve named this high point of our route the Bugle Summit.

but our challenger evidently thought better about showing himself – and since the hunting season had already started might be an unwise move. Nonetheless we heard his heavy hooves on the forest floor as he made his exit. The height of land lay just ahead, so I’ve named this high point of our route the Bugle Summit.

On the south side of the ridge we are descending all the streams flow into the Necanicum River. In less than 21 miles, this river and its tributaries run from a height of more than 2,800 feet in the Oregon Coast Range down to the Pacific Ocean. The upper watershed is dominated by coniferous forests of Sitka spruce, Douglas fir and western hemlock.

Necanicum is derived from Ne-hay-ne-hum, the name of an Indian lodge located on the banks of this lively river. William Clark named this river the “Clatsop River” in January of 1806. In pioneer days the stream was referred to as “Latty Creek” after the pioneer who’s land claim encompassed the area. But by the time the first Post Office was established in 1907, the original Indian name had persevered. In the Clatsop tongue the name is said to describe a gay and animated entity in the mountains – certainly the sprightly nature of this stream has not changed in the intervening years.

The Indians that inhabited the 1100 square miles of coastal plain and river valleys north of Neakahnie Mountain to the mouth of the Columbia were known as the Clatsop Indians. Their territory with its dense forests of fir, pine, spruce and cedar, as well as fertile coastal plains, provided an abundance of game, berries and edible roots. Its fresh and salty waters, including the Columbia, the myriad streams and lakes, and the vast ocean tidelands–teemed with life including many species of salmon, freshwater fish, and shellfish. At the southern end of their realm, the Necanicum’s 85 square mile watershed’s was an important source of food and nurtured groves of giant firs, spruces and pines. These forests were extremely dense with waist-high salal, kinnikinnik, wapato and camas, interrupted by the occasional meadow and berry thickets.

fir, pine, spruce and cedar, as well as fertile coastal plains, provided an abundance of game, berries and edible roots. Its fresh and salty waters, including the Columbia, the myriad streams and lakes, and the vast ocean tidelands–teemed with life including many species of salmon, freshwater fish, and shellfish. At the southern end of their realm, the Necanicum’s 85 square mile watershed’s was an important source of food and nurtured groves of giant firs, spruces and pines. These forests were extremely dense with waist-high salal, kinnikinnik, wapato and camas, interrupted by the occasional meadow and berry thickets.

The Clatsops also considered many of the forest animals and the gargantuan storms that lashed their coastal home to be represent active spirits that coexisted with them in this fog-swathed primeval landscape. Like their cousins the Chinook, they believed that a great wolf spirit Talapus had created salmon to save them from extinction during some primeval near disaster. To honor their wolf deity they observed strict traditions that prohibited them from ever cutting a salmon crosswise. Salmon always had to be cut lengthwise from mouth to tail and the bones had to be returned to the waters for renewal. The consequences for ignoring these customs were dire including burial alive.

The note local ethnographer, James Swan, recounts several creation myths that he heard from the Chinookan residing in the vicinity that relate to these customs. One of them involved an old man who was a giant and an old woman who was an ogress. In the story, when the old man catches a fish and attempts to improperly cut it sideways, the woman cries out that he must cut the fish down the back. The man ignores her pleas and cuts the fish crossways. The fish changes into a giant bird that flies away toward Saddle Mountain on the northern Oregon coast. The man and woman go in search of the bird. One day while picking berries, the woman discovers a thunder-bird’s nest full of eggs. The woman begins to break the eggs, and humans appear out of the broken shells.

Unlike the Calapuyans, the Clatsops were non-nomadic and built permanent low-roofed, partitioned lodges of cedar planks. Their canoes were also made of cedar logs, hollowed out by fire, then carved and finished with stone or bone tools. Food bowls and utility vessels were made from stone, wood, bone and shell. Mats and baskets for gathering and storage were woven of hide, vine, grass, roots and bark.

Settling the Necanicum River valley:

Henry and Andrew Makela, two Finnish fishermen from Astoria first spotted the Necanicum valley while on a hunting trip in 1891. With their newly acquired anglicized surname of Hill (the English translation of “makela”) they decided to homestead the valley. According to their descendants, the community never had more than about 50 inhabitants, or about ten families. It was, for all concerned a mere “hamlet”, hence it’s name to this day.

School was held in one of the homes until 1908, when the hamlet built a new schoolhouse and hired Marie Pottsmith, a 26 year old teacher earning tuition to attend the University of Oregon. Packing her bags she proceeded by train from Salem to Portland, and from there by steamer to Astoria, and by wagon down to Seaside.

There she learned that to reach the hamlet whose inhabitants she was to instruct would require a further 12 mile of rough inland travel to reach Necanicum, and from there she would have to travel another eight miles on horseback into the mountains to reach her new home.

In her journal she recorded how one of the old-timers had informed her that, “the postman waited here as long as he could before he drove to Necanicum with the mail. They don’t have any electric lights out there and they have to travel early. He wanted to get back before dark.” Another helpful soul then volunteered as to how, “the people in Hamlet are Russian Finns and you have to eat black bread and sour milk and maybe you’ve got to sleep with some of the kids, too.” Not to be too encouraging he added, “There are cougars up in those mountains!”

So the next day saw her heading inland from the beach on a heavy buggy with her bags stowed alongside. At Necanicum she met up with the mail carrier, on whose horse she made the final eight miles up the muddy track. On the way they overtook a team of packhorses heading the same direction with “the factory-made furniture” that was, according to the mail-carrier intended to furnish her room – it was the first professional made furniture to enter the hamlet. All the other furniture up until then had been made by hand by the pioneers.

The community, it turned out was not much more than the schoolhouse and several farms nearby – each with their 160 acres of homesteaded land. School was taught from 8 AM with scant time for lunch and recess so that the kids could help with the haying and huckleberrying. On one occasion she and another local women trekked six miles up a rough trail, scrambling over fallen logs and pushing the ever encroaching foliage aside to reach Elsie, where her companion had friends she wanted to see.

In her journals she relates the tribulations of the pioneer women, recounting how they took care of the homestead when the men were off fishing for a little cash. Single-handedly they raised the kids, tended the livestock and withstood the rigors of a pioneer life that left little room for error or respite. Bringing in a herd of cows lost in the fog, could result in a damp night spent sleeping rough in Oregon’s primeval gloom. Childbirth meant an arduous horseback journey all the way to Astoria, or as happened, giving birth by the side of the track and waiting while the husband rushes the newborn babe to the nearest farmhouse and returns with help to transport his supine wife to safety.

Bugle Summit to the Headwaters of the North Fork of the Necanicum River:

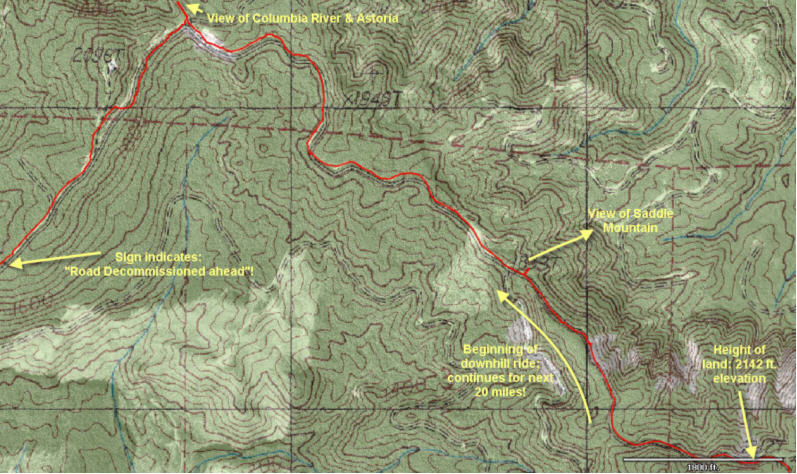

Just beyond the Bugle Summit the road begins to drop, and it basically continues dropping all the way to the ocean more than 20 miles away. As you descend, look northwards and you will see a spectacular view of Saddle Mountain.  To the Northeast you can see Wickiup Mountain and Elk Mountain. Separating Saddle Mountain from the range bordering the Columbia River are Young’s River and the two forks of the Klatskanine River.

To the Northeast you can see Wickiup Mountain and Elk Mountain. Separating Saddle Mountain from the range bordering the Columbia River are Young’s River and the two forks of the Klatskanine River.

As you continue your westward descent you will have opportunity to view the mountains to your south. This cluster of mountains lies in a triangle between US 26 to the North, the Nehalem River to the East and Nehalem Bay to the South. To the east lies Kidder’s Butte – one of a pair of peaks exceeding 2200 ft in elevation. In the immediate foreground is the aptly named Sugar Loaf Mountain – a perfect sugar cone that reaches 2680 in elevation. And in the distance lies a distinctive peak with what appears to be two horns reaching up to 3057 feet: Onion Peak. Beyond Onion Peak lies Ecola State Park and the Pacific Ocean.

At a distance of 4.25 miles from the start you will pass a decent road merging in from the left at an elevation of 1874 feet. Proceed straight. At 5.3 miles from the start we come to a large intersection, with one option opening to our right and crossing the ridge to the north side, the other option curves to the left. We will proceed left and drop down slightly. But beyond the road rises again , and at 5.6 miles (from the start) it ascends to an intersection (at an elevation of 956 feet) with a spur entering from the north. Afterward, it immediately drops down into the original road bed again and begins a rapid straight descent. On the way (5.9 miles) you will pass a sign that the road has been “decommissioned ahead”. Since you’re on foot or on a bicycle you can ignore the warning. Towards the end of the slope the road emerges into a clear cut area with views to the south and the road appears to drop steeply down the slope. Be careful here as the road conditions can get challenging and a few of us have ended up sprawled in the mud on this stretch. Towards the bottom(6.1 miles) , the road turns sharply to the right and swings around a bend.

At 5.3 miles from the start we come to a large intersection, with one option opening to our right and crossing the ridge to the north side, the other option curves to the left. We will proceed left and drop down slightly. But beyond the road rises again , and at 5.6 miles (from the start) it ascends to an intersection (at an elevation of 956 feet) with a spur entering from the north. Afterward, it immediately drops down into the original road bed again and begins a rapid straight descent. On the way (5.9 miles) you will pass a sign that the road has been “decommissioned ahead”. Since you’re on foot or on a bicycle you can ignore the warning. Towards the end of the slope the road emerges into a clear cut area with views to the south and the road appears to drop steeply down the slope. Be careful here as the road conditions can get challenging and a few of us have ended up sprawled in the mud on this stretch. Towards the bottom(6.1 miles) , the road turns sharply to the right and swings around a bend.

Suicide Curve:

As we round the corner we will continue to make good time on fairly unobstructed roadway, working our way to the back of a ravine that marks the top of the North Fork of the Necanicum River. There are more warning signs and finally we come upon the penultimate barrier (6.6 miles): the lined up tree trunks blocking the road. You can skirt by them on the right and then ride carefully to the EDGE . This is what we’ve affectionately dubbed the Suicide Curve.

As we round the corner we will continue to make good time on fairly unobstructed roadway, working our way to the back of a ravine that marks the top of the North Fork of the Necanicum River. There are more warning signs and finally we come upon the penultimate barrier (6.6 miles): the lined up tree trunks blocking the road. You can skirt by them on the right and then ride carefully to the EDGE . This is what we’ve affectionately dubbed the Suicide Curve.

In the storm of 1997 these hills suffered massive damage. Much of it is no longer visible as the fallen trees have been harvested and the rest has blended into the forests, but occasionally the massive landslides are still visible like the one we will have to climb down and across at the head of the North Fork of Necanicum River Here’s how to get across safely and without exerting yourself too much…

In the storm of 1997 these hills suffered massive damage. Much of it is no longer visible as the fallen trees have been harvested and the rest has blended into the forests, but occasionally the massive landslides are still visible like the one we will have to climb down and across at the head of the North Fork of Necanicum River Here’s how to get across safely and without exerting yourself too much…

Push your bike out as far as the slope will allow going as far to the right as possible this will allow you to descend a slight slope to relatively bare spot overlooking the drop into the ravine. At this point turn your bike and face it the opposite direction from where you were pointing it before. Now descend the rough ledge in a westerly direction holding your bike on the downhill side of you. The crack you’re using ends about 20 feet down the slope. Once again reverse the direction of the bike and holding it on the outside, proceed to edge straight back along the rock face staying above the stream to where you can cross it easily and climb up the gassy slope on the other side. In all it will take about 5-10 minutes to traverse this “little adventure”. On the far side the slope is grassy as you climb up to the end of the old road. Congratulate yourself, that was the hardest part of the trip (aside from the initial climb to Bugle Summit).

Push your bike out as far as the slope will allow going as far to the right as possible this will allow you to descend a slight slope to relatively bare spot overlooking the drop into the ravine. At this point turn your bike and face it the opposite direction from where you were pointing it before. Now descend the rough ledge in a westerly direction holding your bike on the downhill side of you. The crack you’re using ends about 20 feet down the slope. Once again reverse the direction of the bike and holding it on the outside, proceed to edge straight back along the rock face staying above the stream to where you can cross it easily and climb up the gassy slope on the other side. In all it will take about 5-10 minutes to traverse this “little adventure”. On the far side the slope is grassy as you climb up to the end of the old road. Congratulate yourself, that was the hardest part of the trip (aside from the initial climb to Bugle Summit).

From here on the road is a gentle descent wending its way through a series of unremarkable and easily confused logging road intersections, but this guide should keep you on track. A really nice place for a break is on a narrow promontory that juts out into the ravine you just crossed. I can be accessed just a few 100 yards down the track beyond the Suicide Curve (6.97 miles).

From here on the road is a gentle descent wending its way through a series of unremarkable and easily confused logging road intersections, but this guide should keep you on track. A really nice place for a break is on a narrow promontory that juts out into the ravine you just crossed. I can be accessed just a few 100 yards down the track beyond the Suicide Curve (6.97 miles).

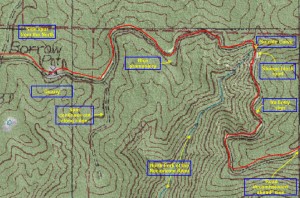

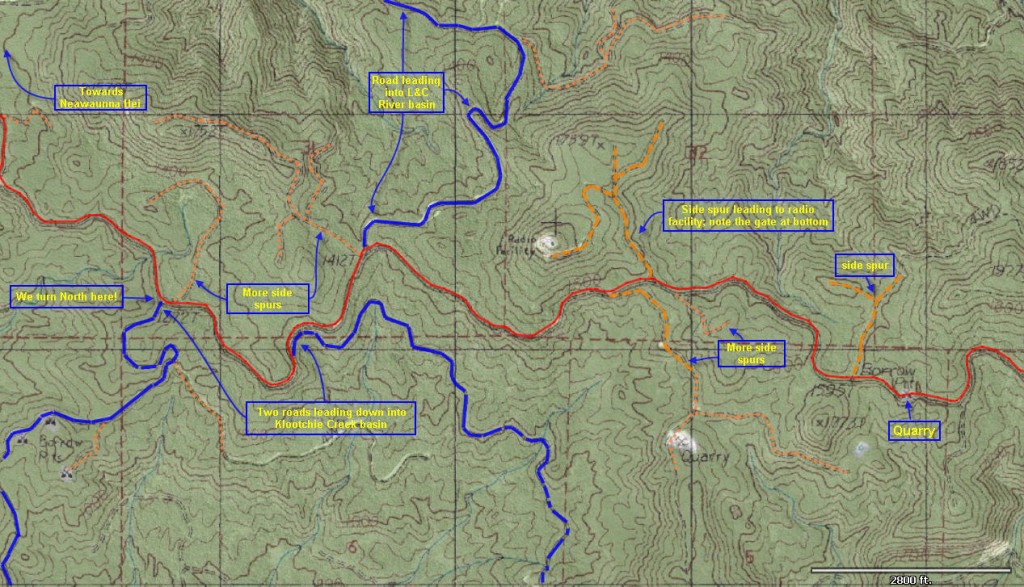

From here we continue to traverse the slope , finally (7.27 miles from the start) we circumnavigate the bowl that marks the top of the North Fork’s drainage . As we turn the corner on the western ridge of this bay, we will pass a spur that extends out on our left. Shortly thereafter, we will pass a small “borrow pit” or impromptu quarry (7.45 miles) used by the logging companies to make gravel for paving these roads (see map below). Another tenth of a mile further (7.6 miles) we will pass a road coming in from the right. You may be thinking that it’s time to change our direction from west towards a more northwesterly direction heading towards Seaside, but be patient – these early routes heading northwest are too far inland to reach Neawanna Heights – the extension of this ridge that will ultimately carry you north to Seaside.

Continue along the road for another 3/4 of a mile and you will come to a triangular intersection where another road that branches off to climb upwards to the right. This side spur (8.3 miles from the start) has a gate near the triangular intersection – that’s because it leads to the top of the knoll directly ahead where it ends at a “radio facility” – probably part of our coastal defense system. We will ignore this option and pass to the left (south) of the knoll continuing westward while traversing the southern flank of the ridge.

Continue along the road for another 3/4 of a mile and you will come to a triangular intersection where another road that branches off to climb upwards to the right. This side spur (8.3 miles from the start) has a gate near the triangular intersection – that’s because it leads to the top of the knoll directly ahead where it ends at a “radio facility” – probably part of our coastal defense system. We will ignore this option and pass to the left (south) of the knoll continuing westward while traversing the southern flank of the ridge.

About a mile below the last intersection (9.2 miles from the start), the road returns to the ridge line where it intersects with one larger road and another smaller road that both reach it from the northern flank of the ridge. The first right hand option is a larger road that leads all the way down to the Lewis and Clark River on the north side of this ridge. The next right hand option (middle option) is a local dead-end spur road accessing the flank of the hill. The left hand option is actually the continuation of the road we’ve been following. Ignoring any temptation to start heading north, we will continue along the left hand option – again skirting the ridge on the southern flank. As we follow this road we will observe another road climbing up the southern flank to meet our road on the left side (9.6 miles from the start). Although we will not use this road, it is noteworthy to point out this it is the first of two roads leading down into the Klootchie Creek basin. The Klootchie Creek basin can be accessed from Highway 26 at the Klootchie Creek Park the prior location of the famed Klootchie Creek Spruce, but that’s a story in and of itself….

Make no mistake this corner of the world is home to the giants, not just Paul Bunyan and his gigantic blue ox, but also several giants that can not just rival our ancient monuments but outshine them in their living grandeur!

For over 750 years a Sitka Spruce had battled torrential storms, weathered fire and pestilence to become the largest Spruce in the US and the World. Growing alongside Klootchie Creek, whose waters flow off the ridge line we are traversing, this giant has grown to the prodigious height of 206 feet tall, and developed a circumference of 56 feet, a diameter of almost 18 feet and a crown that extended 93 feet from the trunk.  But sadly the Klootchie Spruce was badly damaged in the storms that wracked the coast in 2007 and had to be cut down. To put this in perspective Kublai Khan became the ruler of the Mongol Empire at the time that this tree began to reach up into the sky!

But sadly the Klootchie Spruce was badly damaged in the storms that wracked the coast in 2007 and had to be cut down. To put this in perspective Kublai Khan became the ruler of the Mongol Empire at the time that this tree began to reach up into the sky!

But the Klootchie Spruce was not alone as it grew out of the competing canopy to stand towering over the forest and the nurturing Klootchie Creek; nearby a Douglas Fir began reaching heavenward a mere 50 years later – a blink of the eye in a tree’s perspective.  And like its neighboring Spruce this Douglas Fir soon outranked its neighbors to seek out the sun as it grew to giant proportions until November 25, 1962. On that date, after having survived untold storms and hurricane velocity winds during its estimated 702 years of life the giant crashed to the ground during a blustery Sou’wester.

And like its neighboring Spruce this Douglas Fir soon outranked its neighbors to seek out the sun as it grew to giant proportions until November 25, 1962. On that date, after having survived untold storms and hurricane velocity winds during its estimated 702 years of life the giant crashed to the ground during a blustery Sou’wester.

Its death came only a short time after it was officially designated the world’s largest Douglas Fir. At that time it was 15.8 feet in diameter at breast height and measured over 200 feet, 6 inches in height. After its demise the Crown Zellerbach foresters discovered that decay had rotted away the interior of the tree, which was a seedling when Marco Polo began his travels. Ultimately the decay consumed the base of the tree to a height of 38 feet before it succeeded in bringing this near-eternal colossus down.

Its death came only a short time after it was officially designated the world’s largest Douglas Fir. At that time it was 15.8 feet in diameter at breast height and measured over 200 feet, 6 inches in height. After its demise the Crown Zellerbach foresters discovered that decay had rotted away the interior of the tree, which was a seedling when Marco Polo began his travels. Ultimately the decay consumed the base of the tree to a height of 38 feet before it succeeded in bringing this near-eternal colossus down.

Alternative descent to Klootchie Creek Park

Reaching (at 9.6 miles from the start) the top of the first routes into the Klootchie Creek basin we are now approaching the western-most point on our descent. Continuing along the ridge road for another 1/2 mile (to 10.15 miles from the start) we finally arrive at an intersection that faces in a northwesterly direction. To our right a road traverses a west facing slope, while to our left another road crosses the southerly flank of that slope.  Another less used road also enters this intersection from above giving access to the slope above. This is the intersection where we can either descend into the Klootchie Creek basin and the park situated on Highway 26, or we can turn right to follow the more well traveled road along the height of land as it begins to stretch northwards paralleling the coast northwards.

Another less used road also enters this intersection from above giving access to the slope above. This is the intersection where we can either descend into the Klootchie Creek basin and the park situated on Highway 26, or we can turn right to follow the more well traveled road along the height of land as it begins to stretch northwards paralleling the coast northwards.

If you decide that a shorter version of this ridge running delight is required using the Klootchie Creek Park as the terminus will shorten the trip by at least 1.5 to 2.5 hours by eliminating 15 minutes to drive to the north side of Seaside, another 15 minutes back from that location, and the additional hour cycling/ two hours walking to Seaside. The route down from this point to Klootchie Creek is pretty direct but also very steep.  The best descent is this second (more westerly) route since it allows you to descend along the ridge line at the western edge of the basin. That is a more direct route to the park and the bridge that connects to the Sunset Highway (Hwy 26).

The best descent is this second (more westerly) route since it allows you to descend along the ridge line at the western edge of the basin. That is a more direct route to the park and the bridge that connects to the Sunset Highway (Hwy 26).

I have included a map detailing the suggested descent and warning of those intersections/options that would lead down into the Klootchie Creek basin and away from the most direct route.

Descent to Seaside:

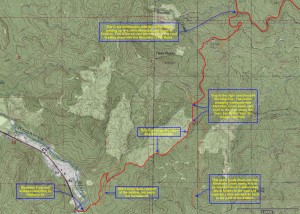

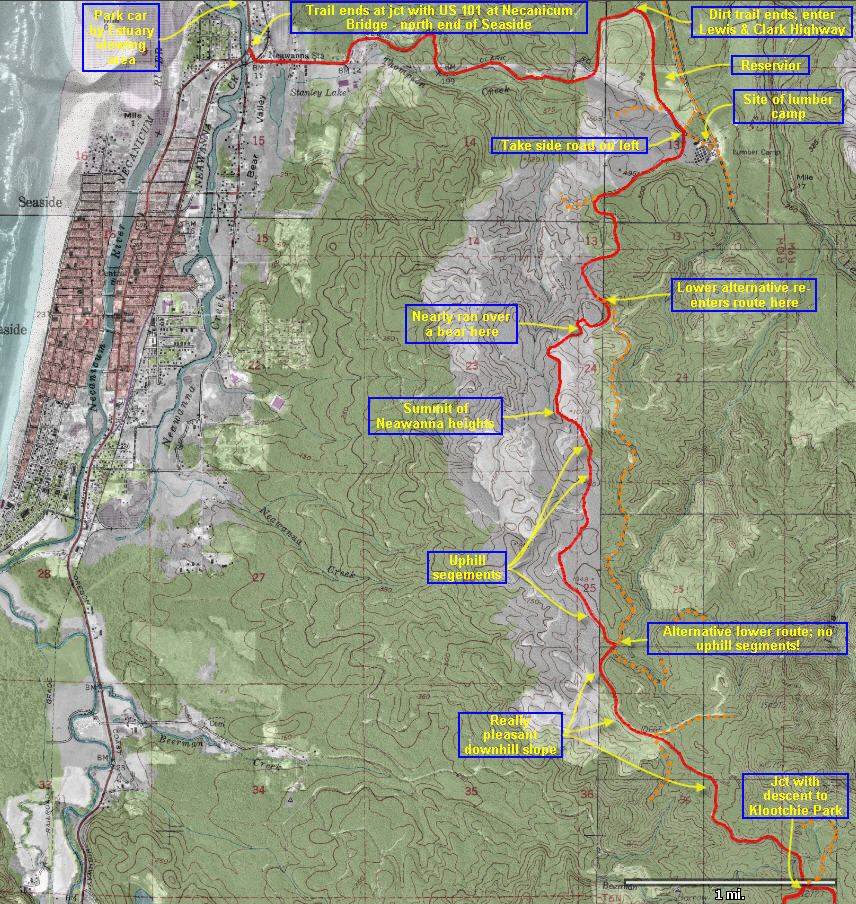

The four way intersection (at 10.15 miles from the start) with the road leading down the western ridge of the Klootchie basin, is also where we turn northwards towards Neawanna Heights, the low mountains directly behind Seaside, Oregon.  From the intersection we follow the road north across the upper slopes of the Beerman Creek basin (westward facing slope) and enter a forested area. Proceeding along a gently sloping road we emerge into a more open area with views of the Pacific ocean, the city of Seaside below us, and Neawanna Heights to the north. The nearby picture shows my friend James facing westward to Seaside and the Pacific Ocean, but pointing to the tall stands of timber crowning Neawanna Heights to the north. This stretch is a pleasant ride, but be careful not to run over any bears if you’re on a bike – we almost did!

From the intersection we follow the road north across the upper slopes of the Beerman Creek basin (westward facing slope) and enter a forested area. Proceeding along a gently sloping road we emerge into a more open area with views of the Pacific ocean, the city of Seaside below us, and Neawanna Heights to the north. The nearby picture shows my friend James facing westward to Seaside and the Pacific Ocean, but pointing to the tall stands of timber crowning Neawanna Heights to the north. This stretch is a pleasant ride, but be careful not to run over any bears if you’re on a bike – we almost did!

About coasting a really pleasant downhill slope for 1.9 miles (11.84 miles from the start) from the Klootchie Creek intersection, we arrive at a junction. Straight ahead the main route crosses the ridge to descend along the eastern face of the ridge. To the left a less used road climbs gently along the western side of the ridge, overlooking a replanted slope. To the right a side spur doubles back to the south.

About coasting a really pleasant downhill slope for 1.9 miles (11.84 miles from the start) from the Klootchie Creek intersection, we arrive at a junction. Straight ahead the main route crosses the ridge to descend along the eastern face of the ridge. To the left a less used road climbs gently along the western side of the ridge, overlooking a replanted slope. To the right a side spur doubles back to the south.

If you take the left hand option it will take you to the top of the Neawanna Heights and from there the road winds back down to the eastern slope of these ocean-facing hills. This route does entail some uphill segments, that (to be honest) I was no longer in the mood for…

Alternatively, you could simply stay on the main track and descend for 2.2 miles along the eastern face of these hills (orange dotted route on map) to where the two routes rejoin (just above the lumber camp that served this area. Just short of that lumber camp keep an eye open for a less used side road heading off to the left. Take this route as it will skirt to the west of the reservoir and almost 16 miles from the start it will intersect with the Lewis & Clark Highway closer to the summit of these hills – that will reduce the final climb required to cross this range. Don’t worry if you miss this turn, the main road north from the lumber camp also leads to the Lewis & Clark Highway – just a bit further to the East.

Finally, it’s time for the “icing on the cake”.  Once you’ve reached this highway it’s a mere 1/2 mile gentle climb to the summit and then it’s a smoothly paved road that runs for almost 2 1/2 miles down off the western slope of these final hills, swinging back and forth in wide loops as it brings you safely to the intersection with US highway 101 – just to the north of the Necanicum Bridge.

Once you’ve reached this highway it’s a mere 1/2 mile gentle climb to the summit and then it’s a smoothly paved road that runs for almost 2 1/2 miles down off the western slope of these final hills, swinging back and forth in wide loops as it brings you safely to the intersection with US highway 101 – just to the north of the Necanicum Bridge.

Ride north for about 1/10th of a mile to the Neawanna Point Coast Natural History Center, Espresso stand and parking lot. The entire trip was about 18.35 miles. I hope you enjoyed it!