In the pioneer days tobacco was sold in pretzel-like twists weighing about an ounce, and referred to as a “carrot”. They were ubiquitous throughout the west, part of every story and included in every important meeting. At the time, everyone focused on what was said or what was hauled away, but on each occasion someone had to break out a carrot of tobacco to make it all official.

In the pioneer days tobacco was sold in pretzel-like twists weighing about an ounce, and referred to as a “carrot”. They were ubiquitous throughout the west, part of every story and included in every important meeting. At the time, everyone focused on what was said or what was hauled away, but on each occasion someone had to break out a carrot of tobacco to make it all official.

Chief Three Eagles was cautiously observing the group. They clearly weren’t Shoshones, Blackfeet, or Peigans. And besides they moved too methodically without taking defensive measures. There was a woman with them and a child. And there was a man painted entirely in black – possibly a powerful shaman. This was clearly not a raiding party. Much of their route had led them through heavily timbered hillsides, and at times across steep slopes that ran along the top of precipitous heights.

Chief Three Eagles was cautiously observing the group. They clearly weren’t Shoshones, Blackfeet, or Peigans. And besides they moved too methodically without taking defensive measures. There was a woman with them and a child. And there was a man painted entirely in black – possibly a powerful shaman. This was clearly not a raiding party. Much of their route had led them through heavily timbered hillsides, and at times across steep slopes that ran along the top of precipitous heights.  Several of their horses fell; one rolled several hundred feet before becoming wedged into a tree. Miraculously the horse shook himself off and walked away uninjured.

Several of their horses fell; one rolled several hundred feet before becoming wedged into a tree. Miraculously the horse shook himself off and walked away uninjured.

Three Eagles sent an Indian boy to lead them into the village. It was the first meeting between these “western” Indians and two distinctly different races: the bearded “white” people and a huge man with black skin – who was a slave, no less!

This meeting has come to symbolize the beginning of a lucrative trade in furs that would span the entire continent, cross a major ocean and then become the catalyst for a burgeoning international trade that has become the hallmark of our current economic age.

This meeting has come to symbolize the beginning of a lucrative trade in furs that would span the entire continent, cross a major ocean and then become the catalyst for a burgeoning international trade that has become the hallmark of our current economic age.

Translation was tough. Lewis conveyed his questions in English to fellow expeditionary Francois LaBiche who passed it on to Charbonneau in French. Charbonneau then asked Sacajawea in the Hidatsa language, and she in turn conveyed the message in Shoshone – which the Salish could understand. Needless to say, much was lost in the translation.

But one matter was not misunderstood. The Salish were low on smokes. But initially they balked at the distinctly harsh flavor of the Virginia-cured tobacco. The Captains quickly mixed in some Kin nick-kinnick, a ground covering shrub whose leaves were smoked across much the the Pacific Northwest. The resulting herbal mixture was less harsh. This was critical since the Indians were in the habit of “swallowing” their smoke – that is, they never permitted any smoke to be exhaled. Under such circumstances, flatulent side effects were inevitable. I can only imagine the sidelong glances that Lewis and Clark exchanged as satisfied farts issued from under the lifted cheeks of their Clatsop or Chinooks hosts.

Tobacco cultivation and ritual usage was deeply rooted in the Indian culture, but with the influx of fur traders from Hudson’s Bay to the lower Columbia River, tastes began to shift. “Traded tobacco” had begun to filter across the north as the fur traders of the Hudson Bay Company and the Montreal-based Northwest company began to send brigades into the interior to expand their trade contacts. Remarkably , the tobacco they brought for the Indians was produced by the Indians in the Brazilian Amazon. “It is a bewitching weed amongst all the natives”, was the opinion of one trader. It was this Amazonian variety that the Indians in the north much preferred. It was moist, sweet in flavor and triple the price.

The so-called “Brazil roll” was first shipped to Lisbon from Trinidad, where English intermediaries purchased it and shipped it to London – where it was transshipped onto vessels bound for the Canada and Fort Vancouver – an overall journey of over 20,000 miles.

The so-called “Brazil roll” was first shipped to Lisbon from Trinidad, where English intermediaries purchased it and shipped it to London – where it was transshipped onto vessels bound for the Canada and Fort Vancouver – an overall journey of over 20,000 miles.

The expansion of trade across the North American continent has for many years been counted as one of the early achievements of the commercial system that we call capitalism.

A vast river of animal pelts was siphoned out of the northern wilds in exchange for a steady supply of mirrors, nails, combs, knives, printed fabrics, buttons and other European utensils. But chief among these trade items were the numerous bundles of Amazonian tobacco that were transported into the interior by the fur trading brigades. Tobacco was more than an incidental element of their inventory; it constituted more than a quarter of the HBC’s inventory of trading goods.

A vast river of animal pelts was siphoned out of the northern wilds in exchange for a steady supply of mirrors, nails, combs, knives, printed fabrics, buttons and other European utensils. But chief among these trade items were the numerous bundles of Amazonian tobacco that were transported into the interior by the fur trading brigades. Tobacco was more than an incidental element of their inventory; it constituted more than a quarter of the HBC’s inventory of trading goods.

Now consider this development in the context of British trading practices elsewhere. In 1780, Warren Hastings, the Governor of India exported the first shipment of opium to China in a bid to stimulate demand for imports, since the Chinese had proven stubbornly disinterested in western wares. In just a few years this stratagem proved so successful that 17-20% of India’s trade revenues were derived from booming exports of the highly addictive opium. And this lesson was not lost on the Hudson Bay Company. They began to import tobacco in larger quantities.

Within a reasonably short time, the demand for tobacco among the Northwest Indians increased so much that a quarter of all the trade goods stored in Fort Vancouver were tobacco! By the summer of 1844 they had 96,000 pounds of tobacco on hand. That’s about 5 lbs for every Indian residing from the mouth of the Columbia up to Celilo Falls – on both sides of the river. But there was just one problem.

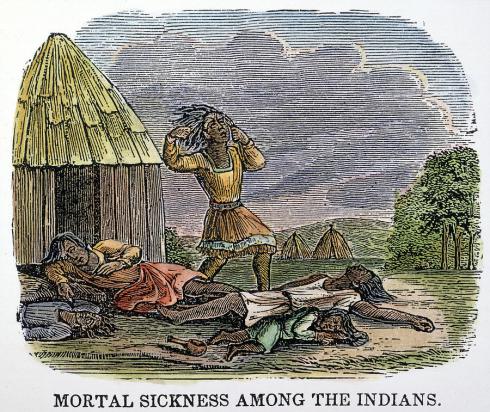

Recent epidemics had just killed off about 90% of those Indians. The HBC strategy had started as a typical colonial exploitation stratagem, but it failed because disease inadvertently exterminated the labor force. The unintended consequence was the collapse of the Indian tobacco demand, and the abandonment of this unique stock of 19th century “trade goods”. The epidemics had the effect of freezing everything in place. Innumerable “carrots” of tobacco waited in vain for their aficionados to turn up, but instead more than 90% of their clientele died.

Recent epidemics had just killed off about 90% of those Indians. The HBC strategy had started as a typical colonial exploitation stratagem, but it failed because disease inadvertently exterminated the labor force. The unintended consequence was the collapse of the Indian tobacco demand, and the abandonment of this unique stock of 19th century “trade goods”. The epidemics had the effect of freezing everything in place. Innumerable “carrots” of tobacco waited in vain for their aficionados to turn up, but instead more than 90% of their clientele died.

In a very demonstrable way, this trove of forgotten tobacco emphasizes the essential role that addictive drugs played in catalyzing trade between populations that had hitherto never traded with each other. Tobacco created an immediate demand that helped to establish an effective market. It wasn’t the combs and calico that launched the trading; it was the tobacco that motivated the Indians to trade their pelts. And soon it would include alcohol, which was already becoming an essential trade good by the 1840’s. The seeds of addiction and alcoholism were sown in the interests of establishing ongoing trade relations with the indigenous tribes. Unfortunately, many were spared the ignominy of addiction by a series of epidemics between 1831 and 1840 that effectively wiped them out. By the 1850’s the Indians had vanished from the Lower Columbia.

A sad tale.

No info of variatal, processing of indigenous tobaccos?

No, you’re right I need to add a blog on the various plants that they used separately and together to mix regional Tobacco blends. One of the most common blends was called Kinni-kinnick, which is a distinct plant by itself, but often served as the base of a regional blend. Other plants mixed in with it included:

* Nicotinia (“Indian tobacco”)

* Red Dogwood (referred to as “Lotzanee” among the War Springs Indians.

* Quinine Bush (Garrya elliptica)

* Bear berry (Arcto staphylos uva ursi)

* Larb (corruption of the French “L’herbe”)

These ingredients were carefully mixed to that each person and each tribe might have very distinct smoking blend. When i write this up more fully on my blog I will consult with Daniel Moermann’s book – which is encyclopedic about Indian uses for plants.

Jim

* Aluck

Great article, thanks!

Interesting article! Thank you for posting it.

Swallowing their smoke resulting in farts? That is totally false.

Do your own research: read the diaries of L & C, the diaries of Alexander Ross, and Rick Rubin’s book, “Naked against the Rain”.

Great article, thank you for writing!

Dear Angela:

I recently published a collection of these stories and associated walking trails, entitled “Hiking from Portland to the Coast” (Oregon State University Press, 2016). The book looks like a trail guide, but each trail is accompanied by a related story. The trails vary from short and kid-friendly to more demanding routes that have you trekking high above the Salmonberry River, and steam railroad logging in the clouds. I call it collecting folk lore, others call it cultural anthropology. To me its what makes a place have meaning, a back story, a history. I collect such cultural history and try to write it down, but there’s too many stories…Jim

What a small world we live in! I’m a docent/interpreter at Fort Vancouver, where I work in the fur trade shop. We feature twist tobacco there, where in 1844 1 beaver pelt would get a trapper 3 pounds of the stuff. I had just sent a reply to your piece about Cronin Creek, where I mention that it was named for my family, which homesteaded there in the 1880’s.

I would love to meet you sometime to talk about your family and about tobacco. I’m in contact with Mary Rose who runs the book shop in your visitors’ center; we’re discussing coming over to do a presentation on my father – long story…

Wow. Now thats something they didnt teach us in U.S. history. At least not in my high school back in the 80’s.

Really enjoyed you article. Thanks for the education. Totally plausible.

You are a gem. I will keep reading some more goodies later. Thanks for the interesting read and recommendations for more!

Working on several more books. The first one is entitled “The most dangerous day of my life.” It’s about escaping an attempted assassination in the jungles of Mindanao. Jim