The early 1800’s were a time rife with social experimentation. Today, it’s hard to see that idealism in the faded daguerreotypes and the stern visages that stare out at us from that far edge of modernity. This was the period when the “Shaker communities” were founded, the Amish established their ways of life, and the English “utopians” were trying out new ideas for societal arrangements. In Germany, the radical protestant sects were promoting communal living arrangements that foreshadowed Karl Marx’s ideas. In most of these communities private property was abolished – even to the point of discouraging marriage in some.

These were heady ideas and they found adherents among the newly arrived German immigrants just then beginning to flood into the country. One of these was Wilhelm Keil, an impressive young Prussian, who arrived in New York in 1831. At the age of 19, he found work as a journey-man tailor and eventually even secured his own shop.

These were heady ideas and they found adherents among the newly arrived German immigrants just then beginning to flood into the country. One of these was Wilhelm Keil, an impressive young Prussian, who arrived in New York in 1831. At the age of 19, he found work as a journey-man tailor and eventually even secured his own shop.

But Wilhelm was fascinated by the raw cross-currents of ideas and science that were pulsing through this new nation. He dabbled in hypnotism and entertained very odd notions of communicating with the dead. But by 1838, he had abandoned the dead and was trying his hand at producing concoctions that promised to deliver everlasting life. He seemed destined to become the quintessential traveling “snake oil salesman”.

But then he discovered the Methodists, and he renounced his more esoteric pursuits. In a ceremony celebrating his adoption of the Methodists’ evangelical calling, he even burned a book of secret cabalistic symbols said to be written in human blood.

Here in American, the Methodists thrived with their programs for building hospitals, schools and other institutions of social uplift. But they were also riven with schisms. In those times of limited communication, it was often the personalities of the movement leaders that set the tone and substance of the ideology, and it was inevitable that charismatic leaders would clash and wreck the unity of their religious communities. Wilhelm Keil became an adherent of the teachings of fellow German, Johann Georg Rapp. Rapp had emigrated to the United States in 1803 and together with his disciples established communities in Pennsylvania and Indiana, whose tenets included renunciation of marriage and advocated celibacy. William went to their newest commune near Pittsburg to study Rapp’s ideas.

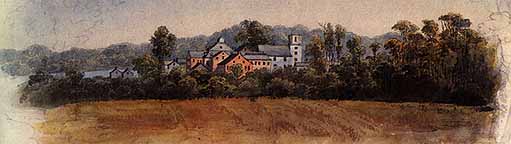

Given the adherence to celibacy and Rapp’s advanced age it is no wonder that when Wilhelm came along and suggested establishing a new community in the promising West, his proposal was well received. When he left Rappist community in 1844 to cross the Missippi and establish his own colony of “Bethel” in Missouri, he had at least 200 disgruntled Rappists in tow. The “Bethelites”, as the new group called themselves, were an industrious lot and soon had erected a nearly self-sufficient community with gristmills, sawmills, a wagon building business and a highly prized brand of whiskey, called the Golden Rule. With their German thoroughness and their reputation for quality they soon became the preferred vendor of pioneer wagons, and for nearly ten years they supplied huge wagons rugged enough to endure the trek through the Great Plains and across the Rockies to distant Oregon. By that time not only had their wagons become a huge success, but their Golden Rule whiskey had become one of the favorite brands of whiskey on the western frontier.

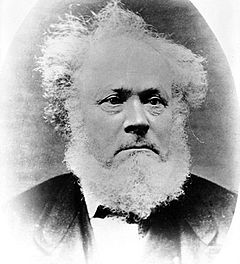

Dr. Keil, as he was known, was the acknowledged leader of this hardworking bunch of Germans. He owned the 6,300 acres upon which Bethel was built, and he was the sole arbiter of their communal decision-making. With his deep-set blue eyes and his fringe beard, he was an unequivocal judge of all he surveyed around him, and for the most part his followers were unhesitating in accepting his leadership. So when William finally caught the “Oregon trail bug” that was motivating so many of his clients, his followers enthusiastically endorsed his recommendation to establish a new colony in that distant country loosely described as Oregon.

But true to his methodical style, everything was to be done in an orderly and well prepared manner. First, he sent out 9 volunteers to scout out the land and select a suitable location for the new colony. Eventually two of the scouts returned and reported that they had selected a prime location near the Lower Columbia, on Willapa Bay. In the meantime, the entire colony had been preparing for their eventual departure. Two hundred and fifty of the “Bethelites” had elected to join the exodus; the rest agreed to stay and continue to manage the community under the principles so well established by their departing leader, Dr. Keil.

Thirty-four great identical wagons were soon under construction and by 1855 they were ready and packed to the brims with all that might be necessary for the crossing and establishing a new colony in that distant land. The colonists were organized into their respective wagons and Dr. Keil’s, eldest son, “Willie” was chosen the drive the lead wagon.

But here’s where our story takes a dramatic twist from the usual Oregon Trail stories. Only days before the anticipated departure Willie fell ill and died! It was a wrenching dilemma, as young Willie had been one of the most enthusiastic proponents of the move to Oregon. With his dying son lying in his arms, Dr. Keil was overpowered by profound remorse and vowed to his fading son that regardless of what happened Willie would not be left behind, and would make the journey with his fellow travelers across the wide prairies all the way to the fabled Oregon and down the Columbia River to Willapa Bay. But even those assurances were not enough to stave off Willie’s inexorable fate and only four days before the scheduled departure young Willie succumbed.

Now under normal circumstances, one might want to overlook the grieving father’s final promises to his dying son, but Dr. Keil was a man of his word in every literal sense of that expression. And so, without a moments hesitation he ordered the Bethelites to construct a hearse, complete with a lead-lined coffin in which he now laid the body of his deceased son. And to prevent the decomposition of his corpse along the long and dusty route, he turned to one of the most traditional German methods of food preservation. And as a result he had the colonists fill the coffin with Golden Rule whiskey, effectively pickling young Willie for all eternity!

But even this final tragedy would not interrupt the carefully laid plans, and with Willie’s hearse in the lead, the great procession of 34 wagons began to roll out of the gates of the compound, exactly on schedule and to the accompaniment of a full marching band. At the forefront of this musical phalanx of horns, flutes, zithers, guitars and drums was a unique Prussian artifact, a “Schellenbaum” that tinkled gaily as it was born along at the head of the column.

A Schellenbaum was a common sight at the head of the Prussian regiments where it was carried in the same manner that the Roman Legions carried their standards – only the Prussian variant sported wing-like protrusion from which hung dozens of bells that jingled in unison to the marching cadence of the standard bearer.

No doubt this exodus was a sight to behold, as the Schellenbaum passed though the gates of the community. Next followed the group’s marching musical corps accompanied by the choral singing of colonists. Leading the column of wagons was the open-sided hearse containing the coffin that held Willie’s pickled corpse. And finally the procession of 34 heavily-ladened wagons rolled ponderously out and headed west. Behind then stood the remaining Bethelites who strained to hear the receding strains of the Methodist hymns, as they faded into the distance under a hot May afternoon. And in front of the the convoy lay the “big muddy” Missouri River and two thousand miles of open prairie, mountains and scorching deserts.

Crossing the Missouri, they first encountered signs of trouble ahead. Here they met wagon trains returning to the safety of the states that told of horrific conditions ahead. It seems that the Sioux had chosen 1855 to initiate a vigorous effort to stop the transcontinental emigration that was disturbing their hunting grounds, encroaching on their traditional home lands and bringing pestilence to their people. They were on the war path to exterminate every convoy of emigrants that they could find, and not as few such expeditions had been utterly massacred. But Dr. Keil was unperturbed. God would watch over them, he assured his followers. He trusted in the Almighty’s wisdom and protection, and on they went – passing more and more panicked settlers running for cover.

By mid-June, the emigrant convoy reached the frontier post just south of the Platte river, at Fort Kearney, where they were adamantly advised to turn back. But Dr. Keil’s response was simply that “the Lord will guide us and preserve us” and after only a couple of days rest the group headed west singing “Das Grab ist Tief und Stille” – a hymn that Dr. Keil had composed expressly for the funeral of his son. One can only imagine the depressing effect that this lugubrious song would have had on the stalwartly marching pilgrims.

And indeed, they didn’t have long to wait for the first signs of trouble to appear. Two days out from the fort, a small band of Sioux were observed. They soon approached, but instead of attacking the convoy, they indicated that they were curious about the odd single carriage that headed up the stolid procession of wagons. Dr. Keil was more than willing to oblige and ordered the elaborate casket to be opened for the Indians to inspect. And as they approached, Dr. Keil instructed his marching band to strike up Luther’s famous hymn, ” Ein’ Feste Burg is unser Gott”. Soon all the terrified emigrants were singing for their lives. At the head of the procession, just ahead of the open hearse the Schellenbaum shook and rattled; its tinkling bells rippling in unison with the singers. At first the Sioux were startled as the guitars, zithers and flutes struck up the tune and the drums and tubas joined the chorus that rang out over the endless stillness of the prairie around them.

The Indians were astounded. Not only was this whiskey soaked deity clearly an instrument of powerful magic, but the harmonic singing of the Bethelites was an entirely new experience for them. Even the magic singing stick was a marvel to them. When the song was over the horse mounted Sioux made it clear they needed an encore, and so the trembling emigrants launched into several German folk songs. Surprised to see that they were still alive after these renditions, they took heart and finished the impromptu concert with a lusty German drinking song. The Indians grinned and made signs that they were very pleased with what they had seen and heard. And with that they vanished into the vast expanses of prairie grasses that surrounded the convoy. Everyone sighed a deep sigh of relief, but wondered what was next. They didn’t have to wait long.

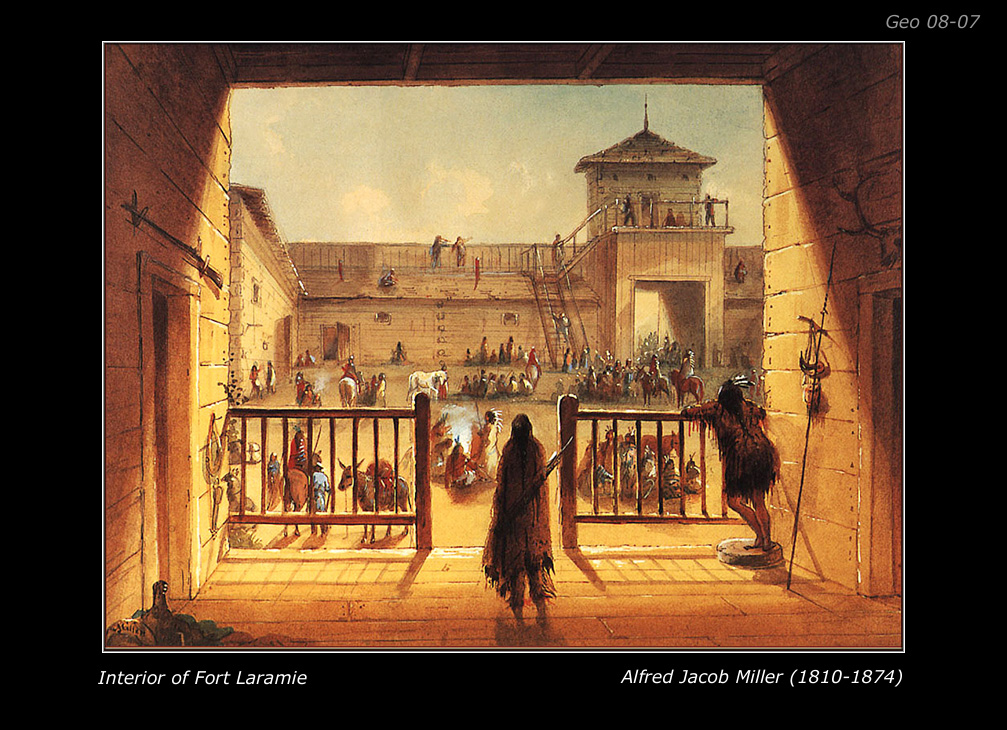

At Fort Laramie, the commandant was insistent that they either return to the East or stayed encamped around the fort so as to have some safety within the walls should the Sioux be so bold as to attack

the fort itself. But once again Dr. Keil demurred and insisted that “The Lord will watch over his own.” There was no stopping Dr. Keil and the emigrants filed past the fort singing their German hymns to the tinckling accompaniment of the Schellenbaum that was held proudly aloft just ahead of the hearse that carried the unfortunate Willie Keil. The soldiers, themselves exposed to the wrath of the Sioux, watched them leave with dread in their hearts, because they knew that scarcely any groups had managed to survive the next leg of the journey – at least as long as the Sioux were on the warpath against the emigrant trains.

Two days later along the the Laramie River, the outriders reported Indian approaches from several angles. The party halted as the warriors become visible along the tops of the ridges. Mounted warriors rippled across the horizon and approached slowly down the hillsides. Dr. Keil rode out to meet the swiftly approaching columns of riders. By signs and limited words the Sioux made clear their desire to see this famed holy man whose body was said to be immersed in the white man’s fire water. This mass encounter occurred not once but several times as they were halted by large groups, at times numbering into the thousands, of Sioux warriors who came to see and hear this strange group of travelers with their unusual cargo and their musical magic.

It is hard to imagine the thoughts of these European travelers as they struggled through the arid landscape dotted with sagebrush and occasional groves of cottonwoods and quaking aspen. How alien and threatening this must have been for those intrepid idealists whose very reason for being there was rooted in a sophisticated culture that was grappling with new models social organization. Here among the stunted Pinyon trees and the flowering larkspur strode determined men and women whose thoughts and conversations grappled with the intellectual roots of an emerging modern society. Here the practical application of communal life and the raw pragmatism of the reformation were translated into a vernacular of pioneer survival. No hunting party would stop to eat until at least one animal had been shot. Every personal liaison was sanctioned by their leader to assure the strength of the coming generations. These were radical ideas anywhere, but they were utterly unique in these desolate valleys.

These idealistic Germans were bold social experimenters that sought to establish a new way of life out of the rawness of the desolate west. And it was here in the remote uplands of present-day Wyoming that they came face-to-face with another people struggling to preserve their own unique way of life.

It was there on the remote banks of the Laramie River, amidst the smoke of campfires and the noisy bustle of the livestock, that the fearsome Oglala braves rode into the pioneers’ camp. Riding silently past the open coffin they gazed at the whiskey pickled corpse of Willie Keil before gathering on the hillside to listen in complete silence as the riveting tones of Dr. Keil’s marching band and the enthusiastically singing congregation echoed across the desolate landscape of Wyoming’s high desert country.

Given the carnage of that summer’s fighting it is almost impossible to visualize this awesome assembly of battle-hardened warriors settling back on their steeds to listen to the pilgrims’ enthusiastic rendition of “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.” And yet through the gathering dusk, they sat as if mesmerized by the unfamiliar sounds of the guitar, the booming of the kettle drums and the steely whispering of the German zithers. They marveled in puzzlement at the birdlike calls delivered by the flutes and clarinets. And even the occasional jingling of the Schellenbaum’s bells reminded them of the delicate sounds of trickling water. And then there was the singing.

These pioneers had a special heritage in common: the long heritage of German choral singing – from its medieval roots in the harmonic arrangements of Hildegard von Bingen, to the intricate scores of Johann Sebastian Bach, and even the rollicking drinking anthems of the Bavarian Octoberfest. The Indians had never experienced this kind of music and were awestruck when the choir broke into an enthusiastic performance of John Wesley’s Methodist hymns. Through the hot afternoon the singing never ceased as the Methodists’ musicians searched for songs to ‘sooth the savage heart’. Eventually, having exhausted their repertoire of hymns, they went on to share an almost endless assortment of popular German “lieder”, popular Rhenish melodies, Prussian marches, Bavarian folk tunes, and even Italian cantatas. But it was the German beer-drinking anthems that ultimately captivated the attentive Sioux. Calling for more, the Indians grinned through their war paint as the singers reprised the roistering verses of “Ach, Du Lieber Augustine” bringing the concert to a climax that would have done any Bavarian bier-tent orchestra proud.

By morning the Indians had dispersed, but from that time on, the Indians would appear leading lost cows back to the Methodist pioneers, leaving freshly killed venison on the trail. Even after they crossed the Rockies into the territories of the Nez Perce, the Cayuse and Paiutes, word of their special status had preceded them and they were welcomed by the Indians. Despite the fact that the summer of 1855 was one of the worst years on the Oregon Trail, Dr. Keil’s wagon trail suffered no harm as they traveled across two thousand miles of wilderness to their destination on Willapa Bay.

By October Dr. Keil’s 34 wagons finally reached the Columbia River and by November they descended the Lower Columbia to reach their destination on Willapa Bay – where their scouts had been busy building structures to house the new colony. Upon their arrival their first act was to extract young Willie from his bath of Golden Rule whiskey and finally put him to rest in the salty soil of Willapa Bay. His grave can be found there still, though the colony itself abandoned that site due to the extreme wet conditions that prevailed along the the Northwest Coast. Within the year they had resettled to the Willamette valley where they established the colony of Aurora in 1857. Aurora survived as a functioning religious community until ten years after the death of Dr. Keil in 1877 when it was disbanded by common consent – a final affirmation of the power of communal consensus.

Wilhelm Keil was my ancestor. His grandson, Frederick William Keil (son of August Keil) was born and raised in Bethel, Mo. He lived to be 97 years old, dying in 1969. My grandfather spoke fondly of his life in Bethel. I enjoyed reading your article about the Bethelites and my great great great grandfather. Very interesting.

Jim, what’s the source of your information about Dr. Keil and the migration west? I’d like to read more about this topic.

Thanks, Robert

There are several sources, including the museum in Aurora, Oregon. But I was mostly inspired by Stewart Holbrook’s book: Far Corner, published by Balantine Books in 1952. Under under “Keil” in the index. A more polished version of this story is in my recently published book Hiking from Portland to the Coast, an interpretive guide to 30 Trails in the North Coast Range.

Jim

I am the great, great, great grand daughter of Wilhelm Keil

Janet Keil Bendure