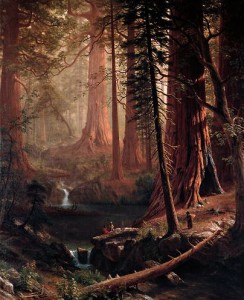

When the first loggers arrived in Oregon they were daunted by the overwhelming vastness of the forests that they beheld. The pine forests of Maine and Minnesota had not withstood their onslaught, but here before them lay a swatch of conifer wilds that extended from Alaska down to Calif ornia. The western portion was mostly populated by Douglas Fir trees blending into the Redwood forests in the south. East of the Cascades and Sierras a wide belt of pine forests lay scattered over most of the western states from the Canadian border down to Arizona and New Mexico. But it wasn’t just the size of these forests that gave the perennially overconfident lumberjacks pause, it was the density of these forests. These enormous trees not only blotted out the sky as they rose majestically hundreds of feet into the air, but between them thick growth of vine maple, rhododendrons, saplings, devils club and dense bushes prevented access. Here in this moist terrarium the trees grew so close together that in a single acre more than five times the number thrived than did in five acres of the gnarliest forests in Maine or Michigan. Indeed, parts of this coastal forest system would later be recognized as the only temperate rainforest in the world, with vegetative density far exceeding any other jungles in the world. Paul Bunyan and Abe had finally met their match in the Pacific Northwest.

ornia. The western portion was mostly populated by Douglas Fir trees blending into the Redwood forests in the south. East of the Cascades and Sierras a wide belt of pine forests lay scattered over most of the western states from the Canadian border down to Arizona and New Mexico. But it wasn’t just the size of these forests that gave the perennially overconfident lumberjacks pause, it was the density of these forests. These enormous trees not only blotted out the sky as they rose majestically hundreds of feet into the air, but between them thick growth of vine maple, rhododendrons, saplings, devils club and dense bushes prevented access. Here in this moist terrarium the trees grew so close together that in a single acre more than five times the number thrived than did in five acres of the gnarliest forests in Maine or Michigan. Indeed, parts of this coastal forest system would later be recognized as the only temperate rainforest in the world, with vegetative density far exceeding any other jungles in the world. Paul Bunyan and Abe had finally met their match in the Pacific Northwest.

The earliest Oregon logging, no doubt began with Lewis and Clarke’s sodden cutting expeditions to gather logs for their shelter on the rainswept Clatsop plain. Four years later the early founders of Astoria were also busy chipping away at the forest fringe to secure material for the rain drenched American trade outpost of Astoria. But none of this represented commercial logging such as the timber industry had practiced from Maine to Michigan.

The first commercial skirmish of man against tree in Oregon’s wet northwest corner has been laid at the feet of Clement Adams Bradbury. As Stewart Holbrook, the familiar Northwest chronicler of this logging era tells it,

“Shortly after noon on the fifteenth of January, 1847, Logger Bradbury, fresh from the York County, Maine, stepped up to a might old fir that grew by the Columbia River some twenty miles east of Astoria, Oregon and hard by the new sawmill of W. H.H. Hunt. He observed the tree’s butt, which was eight feet in diameter, and he looked upward with something of awe to a top that seemed near the clouds.

But Bradbury was a logger. He spat on his hands, took in the lay of the land, and notched his undercut. When he had cut about sixteen inches into the tree, he was surprised, then alarmed by a “copious flow of pitch that would nigh fill a hogshead barrel.” So great was the run of pitch that the amazed Bradbury quit the tree. He returned to it next day, however, when the pitch flow had ceased, and finished the job. According to John Minto, a noted observer of the time, Bradbury soon became “one of the best axmen and loggers along the river.” He learned to cut his stumps high”.

The early loggers soon saw that this was logging on a different scale. Their past experiences did little to prepare them for the density of the woods, the roughness and sogginess of the soil. Despite the near constant rain, the rivers of the Pacific Northwest were not well suited to floating rafts of wood downriver, although this traditional approach was used on a number of inland rivers, such as the Clearwater in Idaho, and elsewhere in the North Cascades. But throughout much of the region the rivers were small and shallow. Transporting the logs over icy roads or on sleighs was also not feasible in this temperate climate. Even the horse drawn big wheeled carriages that could lift the big Minnesota pines off the forest floor to be dragged out, didn’t work in our extremely muddy and rough terrain.

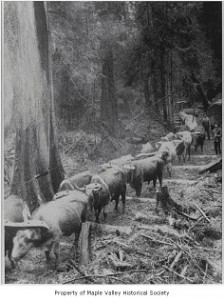

So the loggers soon turned to that ancient precursor of the bulldozer, the ox. Here in the Northwest they were referred to as “bulls” and for the next fifty years these primeval beasts did most of the logging west of the Cascades. But even with these industrial- strength pulling machines, the huge logs that they sought to extract from the slopes above the Columbia River tended to get buried in the soft ground, bringing even the most determined team of bellowing oxen to a standstill. And to avert getting mired, the loggers soon learned to line the route with smaller logs laid across the drag route thus keeping the logs from sinking into the soft soil. This came to be called a “skid road”.

They say it was a sight to behold. Imagine a big cut through  the forest. The oxen have churned the ground into a soupy mess, and all along the shaded alley logs have been laid across the muddy ground to form a log road. By now they are sunk deep into the muck and are scarred from the passage of behemoth logs being dragged across them. In the distance you can hear the colorful profanity of the bull whacker threatening to get really creative with their entrails if the bulls do not “lean on her”.

the forest. The oxen have churned the ground into a soupy mess, and all along the shaded alley logs have been laid across the muddy ground to form a log road. By now they are sunk deep into the muck and are scarred from the passage of behemoth logs being dragged across them. In the distance you can hear the colorful profanity of the bull whacker threatening to get really creative with their entrails if the bulls do not “lean on her”.

Grunting with indignation the oxen begin to descend the muddy avenue straining forward in a stately procession of muscular exertion. Along side the “bulls” the bullwhacker strides alternately cajoling, caressing and castigating his team – jabbing them with his goad stick when all other exhortation fails. The red, black and spotted brutes have now gotten the enormous load moving, sliding over the sunken logs. Running just behind the oxen and in front of the rumbling load, the skid greaser pours thick black oil on the smoking cross logs to reduce the friction. In his recollections of the early logging, Stewart Holbrook remembers the old timers huddling around their camp stoves and decrying the day that steam engines drove the oxen from the forest. To these pioneer bull loggers the sight of these massive creatures pulling impossibly huge logs out of the primordial muck was one of the noblest sight they’d ever seen.

The “skid roads” crisscrossed the upper slopes of the forest, but as they approached the bottom of the slope they all converged along the banks of the Columbia. At the river’s edge the area was a wet and dismal battle zone of converging skid roads – a wasteland of mud, wood, water and littered all around with the industrial detritus left by the loggers. No wonder that the term “skid road” would come to be adapted to “skid row” a term used to describe the tidewater haunts of the poor and destitute found throughout the emerging urban centers of the Pacific Northwest.

The “skid roads” crisscrossed the upper slopes of the forest, but as they approached the bottom of the slope they all converged along the banks of the Columbia. At the river’s edge the area was a wet and dismal battle zone of converging skid roads – a wasteland of mud, wood, water and littered all around with the industrial detritus left by the loggers. No wonder that the term “skid road” would come to be adapted to “skid row” a term used to describe the tidewater haunts of the poor and destitute found throughout the emerging urban centers of the Pacific Northwest.

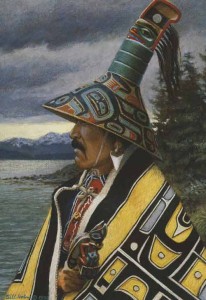

The steam engine would indeed transform logging beginning at the sawmill and eventually the pushing deep into the forest logging operations. Hereabouts, it all began when Messrs. Reed, Abrams and Coffin recently arrived from New England in 1850 and set about demonstrating their new sawmill technology in a clearing south of the growing community of “Portland”. In this clearing that also served as a casual camping ground of several transient Indians group, they set up a boiler and the steam driven sawmill. The Indians hearing that the new arrivals were going to demonstrate a machine that could cut wood without using water, were also eager to watch this spectacle. It soon turned into a festive occasion, according to contemporary accounts. The women donned their dentalium beads and the braves gathered standing stoically wearing their Cinook-style conical hats.

Undoubtedly, they saw the smoke coming from the stack and probably heard the sizzling steam in the boiler. But it appears that they were wholly unprepared for the the lumberman’s traditional way of starting out the day’s work with a steam sawmill. As the operators let loose with the steam whistle, some two hundred Indians fled into the woods in utter panic. It was days before they returned to the vicinity of the mechanical monster with the infernal screech. Despite its frightening appearance the efficiency of this new technology soon helped Portland to thrive, as it strove to But with the efficiency of the steam sawmill at their disposal Portland soon thrived.

But steam technology was big and cumbersome and it would require a lot of tinkering before these whistling monsters would invade the forest. But the vision was there and soon there were several innovators trying to adapt the steam engine to the task of pulling the wood out of the swamp. The first to succeed was John Dolbeer, a partner in the Eureka-based sawmill of Dolbeer & Carson. Dolbeer was a gifted mechanical engineer who was convinced that using a steam engine in the forest would be far more efficient than the slow process of marching oxen in and out of the woods. Throughout the sixties and seventies he worked on trying to adapt the steam engine, and finally in 1881 he built a new machine that would forever change the way logs were pulled out of the forest.

The new steam engine had a vertical boiler, a single cylinder and a horizontal engine with a drum. Dolbeer bolted the new machine to a sled made of timbers and had the oxen drag it into the forest. The bull whackers were amused by the notion that this pathetic contraption would displace even one yoke of bulls. The story goes that the bullwhacker sat on a stump chewing tobacco and making derogatory comments. But then Dolbeer cinched up one of the vast redwood logs. Next he opened up the engine and engaged the drum. The log is said to have jolted up and was soon bouncing its way toward the steam donkey. I don’t know if the bullwhackers realized it at the time , but this demonstration spelled the end of bullock logging.

The new steam engine had a vertical boiler, a single cylinder and a horizontal engine with a drum. Dolbeer bolted the new machine to a sled made of timbers and had the oxen drag it into the forest. The bull whackers were amused by the notion that this pathetic contraption would displace even one yoke of bulls. The story goes that the bullwhacker sat on a stump chewing tobacco and making derogatory comments. But then Dolbeer cinched up one of the vast redwood logs. Next he opened up the engine and engaged the drum. The log is said to have jolted up and was soon bouncing its way toward the steam donkey. I don’t know if the bullwhackers realized it at the time , but this demonstration spelled the end of bullock logging.

But what no one realized at the time was that it would usher in a whole new system of logging that would literally turn the process on its head. No longer would the logs be dragged downhill to the water, but with the introduction of motorized winches the logs would soon be logged uphill to loading platforms perched on the top of ridges. In the history of logging and forestry the development of the steam donkey was the equivalent to the invention of the printing press. It was a “disruptive” invention that made everything that came before obsolete!

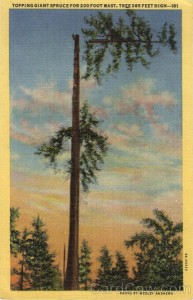

It can be said that the steam donkey gave birth to modern logging. But more importantly, this new technology enabled yet another wave of inventions and process improvements that carried the industry into its modern incarnation. The first of these was the development of “ground lead logging”, whereby the logs were dragged, or “yarded” along the ground to the spot where they would be loaded for the trip to the saw mill.But it wasn’t long before someone came up with an even better system, or “high lead logging”. Instead of dragging the logs along the ground they designed a method for hauling them with one end suspended above the ground to keep it from getting stuck. To do this they had to select a tall well situated tree to use as the “high-lead tree”. From the top of this spar they hung a pulley block and strung a cable through it to the steam donkey. In this way a log could be hauled to the loading area with one end in the air, staying free of the stumps and the underbrush. This new approach gave rise to one of the most celebrated jobs in the industry, the “high rigger”. He would strap on a big belt that he looped around the tree, on his feet were boots with special claws for gripping the side of the tree, and from his belt hung his saw. Continuously moving the belt up the tree as he climber the high rigger would eventually stop after ascending about 200 feet. Here he would proceed to cut the top of the tree off. This was an incredibly dangerous job and therefore it garnered the most prestige in the lumberjack hierarchy. High riggers were known for performing al l kinds of antics after successfully removing the top of the tree without killing themselves in the process. Several were reputed to have stood on their heads on the top of the decapitated spar, while other with less classy tastes took advantage of the great height to drench their fellow loggers. But not all were so lucky. In 1930, the St. Helens newspaper reported on the tragic case of Guy V. Nightingale, who while in the employ of the Clark Wilson Lumber Company in the vicinity of Camp Wilark fell 125 feet to his instant death. It appears that when he attempted to cut the tree top, the tree split and his belt was instantly severed. He was seen to clutch the tree for an instant, but then fell to his death.

l kinds of antics after successfully removing the top of the tree without killing themselves in the process. Several were reputed to have stood on their heads on the top of the decapitated spar, while other with less classy tastes took advantage of the great height to drench their fellow loggers. But not all were so lucky. In 1930, the St. Helens newspaper reported on the tragic case of Guy V. Nightingale, who while in the employ of the Clark Wilson Lumber Company in the vicinity of Camp Wilark fell 125 feet to his instant death. It appears that when he attempted to cut the tree top, the tree split and his belt was instantly severed. He was seen to clutch the tree for an instant, but then fell to his death.

Soon someone had the bright idea to top two spar trees and rig them both with pulleys and thus was born the sky-line system that is still in use today. It worked like a looped laundry line with logs dangling below the aerial relay. In this way the logs were lifted into the air and could be zipped up and down slopes, across canyons with great speed and efficiency. Trains and later trucks would complete the modernization of logging, but the twentieth century transformations deserve their own blog.