In the summer I often get out into the woods during the work-week which occasionally finds me having to contend with the loggers that make their living in these same forests. As you have probably realized by now, this writer tries not to takes sides on the debate of whether logging is good for our community or not. I will leave it to others to determine what are good forestry practices and what aren’t – and I hope they make prudent choices that allow the forest to be valued for its many eco-system services, not just exclusively its recreational values or its industrial values.

In the summer I often get out into the woods during the work-week which occasionally finds me having to contend with the loggers that make their living in these same forests. As you have probably realized by now, this writer tries not to takes sides on the debate of whether logging is good for our community or not. I will leave it to others to determine what are good forestry practices and what aren’t – and I hope they make prudent choices that allow the forest to be valued for its many eco-system services, not just exclusively its recreational values or its industrial values.

That disclaimer aside, let me also admit my fascination with the rough-hewn independence of our brawny Northwest logging culture. And nothing exemplifies that more than the quintessential Pacific Northwest tradition of the “gyppo logger”.

In the Pacific Northwest, the tradition of assembling small bands of entrepreneurial woodsmen harkens as far back as the adventures of the American Fur Company and more recently the infamous “Wobblies” of the early 20th century. The most recent incarnation of that pioneering spirit can clearly be found amongst that small scruffy segment of the forest products industry colloquially known as the “gyppo loggers”. Gyppo logging usually refers to a small, independent “outfit” of lumbermen that have contracted out the harvesting of timber. Typically, such an “gyppo show” will number no more than a dozen rugged woodsmen using battered skidders, loaders, caterpillars, a fire truck, a “crummie” to haul the crew in and out, and a portable yarding tower to pull massive amounts of lumber out of the most difficult terrain imaginable.

The term gyppo originally derives from the old railroad building days when groups of laborers would desert their employers only to form a small cooperative that competed for the work contracts, thus “gypping” their former employers of the work. The success of these entrepreneurial companies is due to work hard, keeping costs low and undercutting the bigger operators by just enough to win the bid, but not so low as to lose their profit – it took both experienced cost estimation and an experienced and determined crew.

At the bottom of the logging show’s hierarchy is the chocker setter, who spends his day dragging a thick “chocker cable” across the steep slope of fallen trees. This is exhausting and dangerous work clambering through the poison oak, the devil’s club and the dense tangle of vinemaple branches. All around them are newly “bucked” logs (stripped of branches) lie precariously intertwined on the steep slope. Dragging the chocker cables behind him, the setter then scrambles underneath the precariously perched logs and wraps the heavy cables around one end of the fallen log. Once attached he scrambles back seeking relatively safety away from the collared trunk and issues two blasts on his radio to signal to the yarder that he can tighten the “skyline”.

With a throaty roar the yarder’s winch tightens the skyline and this massive cable lifts off the slope with the chocker cables dangling off it like massive leashes dangling from a laundry line. As the skyline tightens high above the slope, the logs tethered to the chocker cables lurch off the debris-strewn slope. The choker setters watch this process warily as other logs are shifted and slide into new configurations. If too much strain is put on the chocker cables they can snap tossing these huge lengths of lumber onto the slope as if playing a giant’s game of pick-up-sticks.

With a throaty roar the yarder’s winch tightens the skyline and this massive cable lifts off the slope with the chocker cables dangling off it like massive leashes dangling from a laundry line. As the skyline tightens high above the slope, the logs tethered to the chocker cables lurch off the debris-strewn slope. The choker setters watch this process warily as other logs are shifted and slide into new configurations. If too much strain is put on the chocker cables they can snap tossing these huge lengths of lumber onto the slope as if playing a giant’s game of pick-up-sticks.

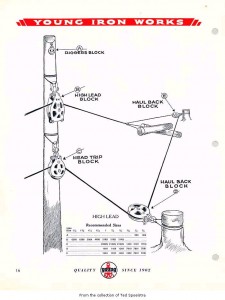

At the other end of this cable sits the yarder operator. He’s the one that has to carefully raise the cables and ensure that the collared logs rise off the slope without snapping the cable, dislodging other logs. If the cables extend too far to either side it might put too much lateral pressure on the line. That’s when it needs to be moved. Using a caterpillar they will relocate the distant anchor point about 5 degrees beyond the prior position. There they will anchor it to a new stump, and then rearrange the tail blocks and rigging to achieve the right declension over the canyon.

Once the double bleeps of the radio signal that the logs have been fastened the yarder fires up the winch and begins to haul the dangling logs up the slope and deposits then on the nearby loading deck.

That’s where the loader operator demonstrates his skills: sorting the logs, stripping off the remaining branches and loading them on to the waiting log trucks. The loader resembles a huge battered crab from whose elevated arm dangles an enormous claw. The claw can be flung up to fifty feet to clutch at logs strewn across the loading deck – that large flat area resembling a helipad upon which the gathered wood is dumped. Like a beaver inspecting his trove of sticks, the loader hoists his logs closer for inspection and sorting. Sliding the clamp deftly down the trunks he strips off the remaining branches and then tossed the log aside for later loading or he carefully positions it onto the back of the waiting log trucks. If the wood is not of sufficient quality it will go to the plywood mill, otherwise it will go to the mill that cuts the structural timber. Sorting the wood effectively can make or break a gyppo operator.

That’s where the loader operator demonstrates his skills: sorting the logs, stripping off the remaining branches and loading them on to the waiting log trucks. The loader resembles a huge battered crab from whose elevated arm dangles an enormous claw. The claw can be flung up to fifty feet to clutch at logs strewn across the loading deck – that large flat area resembling a helipad upon which the gathered wood is dumped. Like a beaver inspecting his trove of sticks, the loader hoists his logs closer for inspection and sorting. Sliding the clamp deftly down the trunks he strips off the remaining branches and then tossed the log aside for later loading or he carefully positions it onto the back of the waiting log trucks. If the wood is not of sufficient quality it will go to the plywood mill, otherwise it will go to the mill that cuts the structural timber. Sorting the wood effectively can make or break a gyppo operator.

A single logging show can produce an average of a dozen or more log truckloads per day – or the equivalent of enough wood to complete 5 new homes. Truckers get paid by the load – averaging around $150 per load. Since they need more than $300 per day to cover their costs, they have to complete at least three loads per day. Usually the truckers work in rotation, so that hopefully they can achieve their desired quota every other day. But key to this regimen is getting the logs to the mill as quickly as possible, thus increasing the chances of snagging another load before shutting down for the night. This is why the loggers are known to race down the logging roads as if they owned them – which in fact they do! If you’re brave enough to navigate the logging roads during the weekdays, keep your head and give these barreling giants the biggest berth you can. Despite my years of experience driving these roads, I avoid active logging routes as much as possible and when that’s not possible I honk approaching every blind corner and hug my side of the road to make as much room as possible for the trucks. Remember that’s more than 40 tons of truck and logs coming at you!

A single logging show can produce an average of a dozen or more log truckloads per day – or the equivalent of enough wood to complete 5 new homes. Truckers get paid by the load – averaging around $150 per load. Since they need more than $300 per day to cover their costs, they have to complete at least three loads per day. Usually the truckers work in rotation, so that hopefully they can achieve their desired quota every other day. But key to this regimen is getting the logs to the mill as quickly as possible, thus increasing the chances of snagging another load before shutting down for the night. This is why the loggers are known to race down the logging roads as if they owned them – which in fact they do! If you’re brave enough to navigate the logging roads during the weekdays, keep your head and give these barreling giants the biggest berth you can. Despite my years of experience driving these roads, I avoid active logging routes as much as possible and when that’s not possible I honk approaching every blind corner and hug my side of the road to make as much room as possible for the trucks. Remember that’s more than 40 tons of truck and logs coming at you!

Thank you so much for such a detailed and vivid description of the gyppo loggers of the PNW. I grew up in Grays Harbor and logging was our way of life. You brought back a lot of great memories for me. As I child, I would ride in the log trucks with the local drivers. Alot of them were gyppos. Oh, the memories!!!

I’m about to embark on some extensive interviews and may gather more information about this aspect of these lands. It’s a story worth telling!

Thank you so much for this wonderful piece of logging lore! I happen to be translating into French Ken Kesey’s great, gripping novel, Sometimes a Great Notion, which describes the logging word of Oregon’s Coast Range in the 1950s–so, your description has been a great help to understand precisely the phrase “gyppo show.” I’ll be damned if I can find an equivalent in French, though !

I think the sense of word “gyppo” has more to do with independent operator – a subcontractor. It also has a flavor of spontaneity and outside the boundaries of regulated business…or at least that describes those people I know that were involved in such ventures. Rough-hewn men that didn’t care for rules.

My Dad was a gyppo logger in the woods near Granite Falls, WA and later operated a cedar shake mill in Granite. Thanks for the clear explanation of gyppo logging. I passed it on to my daughters.

I think when you said “chocker cable” you meant “choker”, as the cable circles the log like a neck choker. A chocker would put a wedge under a wheel.

Thanks for the spelling correction. You’re absolutely right; I added an extra “c”. Jim

My Dad was at first a gyppo logger in NW Oregon, (Cherry Grove to be precise) and I always thought that it had a lot to do with getting the best deal the logger could from the landowner when negotiating the contract. There was also the potential that maybe not all the logs cut got reported or scaled which increased the profits to the logger of course, but this is just conjecture on my part.

I had the privilege of working in the woods of Northern California for four summers while I was going to college in the early sixties. By then Dad was contract logging for one mill and was no longer considered a gyppo. It was hard, dirty, dusty, tiring work, but at the end of the day very satisfying as you watched the last load head down the hill. I set chokers, worked the landing, drove water truck and did fire watch which included fueling all the equipment after everyone had left for the day. It was always interesting to hear the birds start to call out after the last vehicle was gone and all the equipment shut down. It got really quiet then and gradually you could hear the wildlife. Maybe they were talking all day, but we just couldn’t’ hear them?