In The Hidden Life of Trees, Peter Wohlleben presents a multi-generational perspective on the “old” forests he manages in Germany. Much of the scientific inquiry that he conducted was done under the aegis of Aachen University (RWTH Aachen). In this book he links his own knowledge and scientific inquiry with recent forestry research coming out of British Columbia, Brazil, Australia, the US and Russia. And the conclusions he reaches are very thought provoking.

In this handy little tome, Wohlleben describes the links that synchronize the diverse actions of many trees into a single sentient organism. He methodically examines the resulting behavior of this socially cohesive forest through a variety of perspectives to see if the collective entity shows the essential qualities of sentience.

So what are those essential qualities of sentience? The following questions summarize some of the qualities that he examines.

Can the forest communicate? Can it count?

In the early chapters of the book Wohlleben gives many examples of how trees communicate: through their intertwined root systems, by releasing bursts of scent or by transmitting their conversations along vast subterranean fungal networks.

He also describes a well-known phenomenon that causes groups of trees to coordinate their production of fruit or seeds so that they produces a bumper crop of fruit bodies. The large crop of seeds or pine cones overwhelms the herbivores ability to consume the crop – leaving many fruit-bodies uneaten and able to germinate in the spring.

Douglas Fir cone

In Germany this is called a “mast” year and it is usually followed by a spike in the population of herbivores – since there’s plenty for them to eat. However, in the following year, a dramatic drop in the production of pine cones or seeds causes the populations of deer to collapse. This unique reproductive strategy not only suggests communications between the trees, but also hints at active collaboration, and the ability to count, since these “mast” years do not occur at predictable intervals.

Can a forest smell or taste?

The notion that trees can signal danger to its neighbors by releasing a special scent is astonishing enough, but it gives rise to an even more remarkable question: can trees smell these danger signals – differentiating them from the usual olfactory background scents.

Can a forest learn from memories of prior experiences?

Wohlleben illustrates how the spruce drinks up all the available water but later adopts water frugality. He recounts the differing behaviors of two separate groups of trees: One absorbed and transpired vast quantities of water to grow quickly, while the other retained more water and grew more slowly. It had learned the hard way that coming up dry in mid-summer was unpleasant. This change of behavior in response to prior occurrences suggests that trees have the capability to remember and learn from previous experience. Where is this memory held? What part of the tree community makes the decisions. We’re but babes in the woods when it comes to these questions.

The forest does not practice the Law of the Jungle.

The evidence of Wohlleben’s field observations and the research from his far-flung contributors supports the notion that forests are capable of sharing resources for the benefit of the entire forest community.

The Institute for Environmental Research at RWTH Aachen has even found evidence that the trees synchronize their growth despite differences in the soil conditions and access to sun. It seems that they are all photosynthesizing at the same rate regardless of the different growing conditions. Evidently the forest does not live by the law of the jungle. Among trees the strongest make sure that the weakest are equally successful, since a uniformly strong canopy strengthens the entire forest.

How does “thinning” affect the forest?

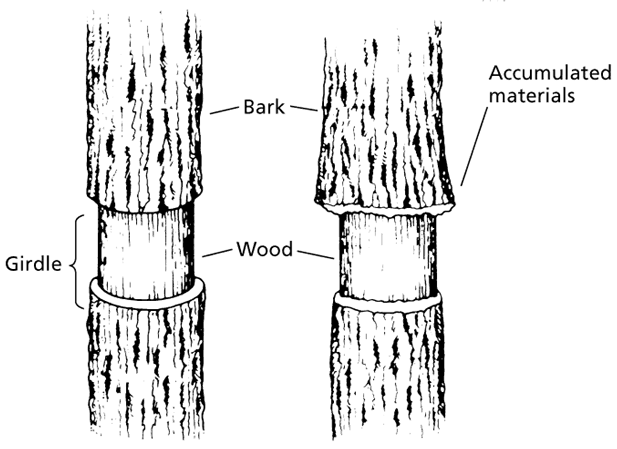

What about “thinning” one might ask? Here in the Pacific Northwest trees are seeded quite close together necessitating an initial thinning within a dozen years or so, and then again after 25-30 years. Wohlleben claims this rips at the fabric of the growing forest. He asserts that when trees are thinned that it breaks their communications since their closest neighbors have been removed. This inhibits their abili ty to develop collaborative strategies to share resources and ensure a dense regrowth of the canopy. He even cites a case where “girdled” trees overcame this attempt at strangulation. The neighboring trees made sure to supply the injured trees with enough nutrients and carbohydrates to overcome their injuries.

ty to develop collaborative strategies to share resources and ensure a dense regrowth of the canopy. He even cites a case where “girdled” trees overcame this attempt at strangulation. The neighboring trees made sure to supply the injured trees with enough nutrients and carbohydrates to overcome their injuries.

I have found that such “girdled” forests also have a much stronger mycelium layer, suggesting that some of the aid is delivered through the mycorrhizal fungal network. From my experience this active mycelium layer also contributes to the proliferation of mushrooms – a fact that is interesting for the mushroom hunter.

The Slow Growth Movement for trees.

Wohlleben’s book delves into forest procreation and the symbiotic role that insects play in this complicated sequence of events. He also explores the age-old dilemma of how to avoid inbreeding – a mortal danger for almost all creatures. And then there’s the “upbringing” (Erzeihung) of the younger trees. It turns out that for many trees it is unhealthy to grow too quickly, and the older generation that towers over the young seedlings can enforce their “upbringing” through the simple expedient of depriving them of light. Scientists have determined that those trees that experience a slow initial growth are much more likely to live longer.

And then there are those trees that have abnormal shapes, like “pistol grip” trees that grow out of the ground at an angle, but then straighten to grow vertically upwards. In the Alps or on steep snowy slopes this bend in the trunk can be due to the pressure of snow combined with rockfall piled against the pliant trunks of seedlings. In the Pacific Northwest it is more likely due to the very slow movement of the ground. In these cases the tree grows straight, but the slowly shifting soil tilts the seedling, which later bends its growth to regain a vertical alignment. Look along the edges of our ravines to see the struggling “pistol- grip” tree trunks. Down in the basin of the ravine, you can observe the agile alders steady themselves as the ground slips by beneath them. The occasional big-leaf maple will anchor itself along the edges of the ravine. But the fir and cedar prefer to stay on the ridge lines where the earth is nearly stationary – in part, because these trees are prone to tipping over after excessive rain turns the soil into pudding and winds pummel their highest branches.

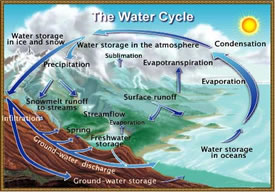

The hydrology of forests.

In one particularly good chapter he examines the forest’s hydrology. He points out that the wide expanse of forested land hugging our coasts is responsible for weather patterns as far as 400 miles inland. By clear cutting these coastal slopes we remove the sponge-like quality of these dense coastal forests to soak up the ocean storms that come thundering out of the Pacific.

For every square yard of forest, the tree canopy can grow up to 27 square yards of leaves and needles. In a good storm that canopy can absorb a couple of hundred gallons of water. Spruce can absorb up to 2.5 gallons of water per square yard of forest during a hefty rainstorm, but two thirds of the water flows off the tree to seep away in little foaming rivulets. Spruce do well in the colder northern hemisphere where the ground water seldom disappears, or on the mountain slopes where heavy rainfall and snow retain more ground water. They’re apt to be spendthrift with water, until they experience a drought. Thereafter, they are careful to retain enough water to tide them through a drought. How do they remember, and where does that memory reside? Peter has some ideas about this, but he urges more research to find the location of a forest’s “judgement.”

The question of relative timescales.

Here in the Pacific Northwest trees can grow to be 800 years old, or older. That’s nearly 10 time the longevity of humans. Does this huge disparity in timescale between trees and humans blind us to the actions of trees? What trees considered an abrupt change, might not even register on our shorter time-frame.

An example of this can be found in the current studies of climate-induced tree migration. Studies in Sweden have found that the Norway Spruce has adjusted its growing range 240 meters in elevation since 2002. Changes in altitude are a good proxy for geographic migration because the higher elevation causes temperatures to drop and the growing seasons to shrink emulating the climatic shifts associated with northward migration. However, recent studies have also revealed that instead of “heading north” trees are adjusting to the warmer and wetter climates by increasing the relative abundance of juveniles. These adaptations appear to be speeding up the trees’ life-cycles instead of shifting the distribution of tree populations northwards.

Given the enormous differences in our timescales, it may not be feasible to determine whether trees will opt for migration or simply increase their life-cycles. In that lengthy time-scale that encompasses a tree’s lifetime, we may need several lifetimes to appreciate the tree’s perspective.

My friend Martin Flatz has a tree like this. The stories about this chestnut tree’s great achievements and disasters are deeply rooted in his family’s oral traditions. It has presided over the annual puppet show for nearly 50 years, and it has seen the comings and goings of owners and refugees for several centuries. Martin’s letters bring news of how it fared in the winter storms. It is a tree of which we might say, it has its own character and has a presence in our lives.

Monetization of carbon accumulation in our forests.

For centuries we have used the forest as a resource and the only way that we estimated its value was to price it out in terms of the dimensional lumber that the tree could produce. After about 60 years the vertical growth of our forest’s trees begins to slows. Traditionally, when the upwards expansion of the forest began to slow, we would summon the loggers.

Older trees grow faster and sequester more carbon than young trees, but this growth occurs at the base of the tree with large bulges oozing down the trunk.

But recent studies have shown that growth actually increases as the tree ages. The tree’s growth was not significant in terms of its height. Instead the studies showed that it came from an ever-expanding trunk. “Rather than slowing down or ceasing growth and carbon uptake, as we previously assumed, most of the oldest trees in forests around the world actually grow faster, taking up more carbon,” said Richard Condit. According to this staff scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, “A large tree may put on the weight equivalent of an entire medium-sized tree in a year.” Just like humans this additional girth shows up as bulging growths that cascade down the trunk.

Increasingly there is heavy competition for the “free” resources that are generated in our “common areas.” Commercial interests are buying up our water, and fossil fuels are polluting our air. Fishermen, farmers, energy companies, recreational users and Indians are competing for these increasingly scarce resources. Clearly we cannot abide the degradation of our atmosphere and must find a way to regulate demand and incentivize increased carbon retention. These pressures may push us to put a price on these free resources, either in the form of a carbon tax or through a cap-and-trade market. If that occurs, users that degrade our atmosphere or use our water will be obligated to restore these resources to their prior capacity. The most direct way to do this would be to create a market that lets carbon emitters purchase carbon retention credits equal to the resource they used. A carbon tax is another alternative approach to pricing these resources and funding initiatives that increase carbon retention.

Mandating some form of compensation for the use of our common resources would immediately change how we perceive and value our forests. The forester would no longer be concerned with maximizing the output of dimensional lumber, but would instead be managing the forest to maximize its carbon retention. Trees would become more valuable as they grew older and increase their carbon absorption. Standing trees would be eligible for an annual carbon credit, that would increase with the size and age of the tree. The creation of carbon retention credits based on carbon retention by trees would turn our coastal forests into a gold mine – as long as producers needed to buy credits to offset their depletion of our “common” resources. If such a market were to be established it would effectively recognize the huge value that our forests create in the form of breathable air, potable water, inland precipitation, and climatic stabilization.

Do trees have their own emotional needs? If so, do we accommodate these needs?

In the introduction to his book, Peter Wohlleben writes about his discovery that trees can experience pain, and have memories. He describes how their live in groups with parents and children in close proximity. In the forests that he manages heavy machinery has been banned since it is destructive to the flora and fauna and also compacts the soil making it harder for the roots and the mycorrhizal networks to propagate. Throughout Germany trees are harvested selectively, and in the forests that Peter oversees only horses are used. He reasons that this also makes commercial sense since a healthier and “happier” forest is more productive and profitable.

Even though we know that trees are living creatures we still categorize them as objects. Should we accord them with rights as we do with other living creatures like pets, and domestic animals? Yet even domesticated animals are slaughtered so that we can use them for our own survival. Why not trees? Is the harvesting of trees a reprehensible activity? Not necessarily, since we too are part of the natural food chain and we cannot survive without using the organic substances provided by our fellow creatures.

The real question is whether we use only what we need and otherwise leave the forest alone to grow in peace, without the disturbances of caterpillars, skidders and heavy trucks that thunder through the trees’ pastoral home like the four riders of the apocalypse. Instead we should begin to consider softening our impact on our forests, by reducing our massive clear cuts, by selecting logging, by using horses rather than machinery and above all by letting trees live “in a way that is appropriate to their species.” That means we should recognize their social needs, and allow them to mingle and to pass on their wisdom to their successors. Some should be allowed to grow old, unharvested, until they buckle under the natural furies of the Pacific storms.

We’ve come along way in the past century with respect to our treatment of mammals and fowl that occupy niches near us in the food chain. Lewis and Clark ate more than 200 dogs during their two year expedition; today we consider such practices to be barbaric. We raise cage-free chickens, and free range lamp, to say nothing about our monumental efforts to restore the Pacific Northwest fish runs. On Oregon’s Mt. Hood logging is severely restricted in the Bull Run watershed. They log selectively and only when it is necessary, and then they use horses equipped with diapers to avoid introducing external organic materials. Is it really such a giant step from where we are today to a gentler, and kinder forestry – especially if the reward systems are reversed and trees are more valuable as carbon repositories, than as dimensional lumber. When standing timber is more valuable than lumber these changes in forest management will inevitably follow. And the Pacific Northwest will experience a renewable resource boom that will reward us for our forests – since they may be the most effective guarantor of North America’s breathable air supply.

Meet your new partners in our effort to sustain the livability of our planet.

This book will leave you with more questions than you started with, but it will also make you feel like you’ve been introduced to a new form of intelligent life that’s been with us all along and may hold the key to our survival. I recommend Peter Wohlleben’s book to those fascinated with the forests, or just those looking for new perspectives on our existing paradigms. Happy reading.

Thus by good looks and timing Guy de Lusignan became the King of Jerusalem in 1186, reigning until 1192. Following his accession to the throne, there was increased fighting with the Ayyubids, who were loyal to Saladin. In 1187 Guy was captured by Saladin and imprisoned in Damascus. A year later he was released, but he was unable to regain his crown, despite strong support from King Richard the Lionheart. In compensation Guy was made the Lord of Cyprus, where he ruled until his death in 1194.

Thus by good looks and timing Guy de Lusignan became the King of Jerusalem in 1186, reigning until 1192. Following his accession to the throne, there was increased fighting with the Ayyubids, who were loyal to Saladin. In 1187 Guy was captured by Saladin and imprisoned in Damascus. A year later he was released, but he was unable to regain his crown, despite strong support from King Richard the Lionheart. In compensation Guy was made the Lord of Cyprus, where he ruled until his death in 1194.

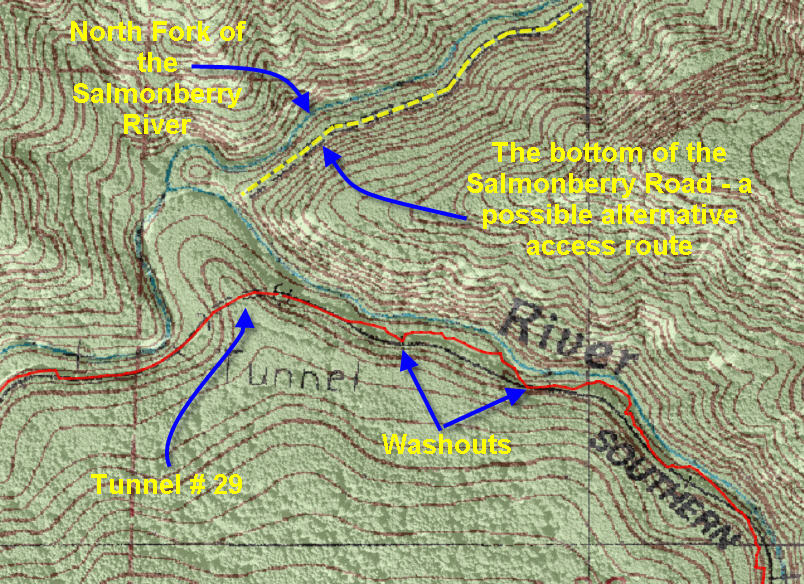

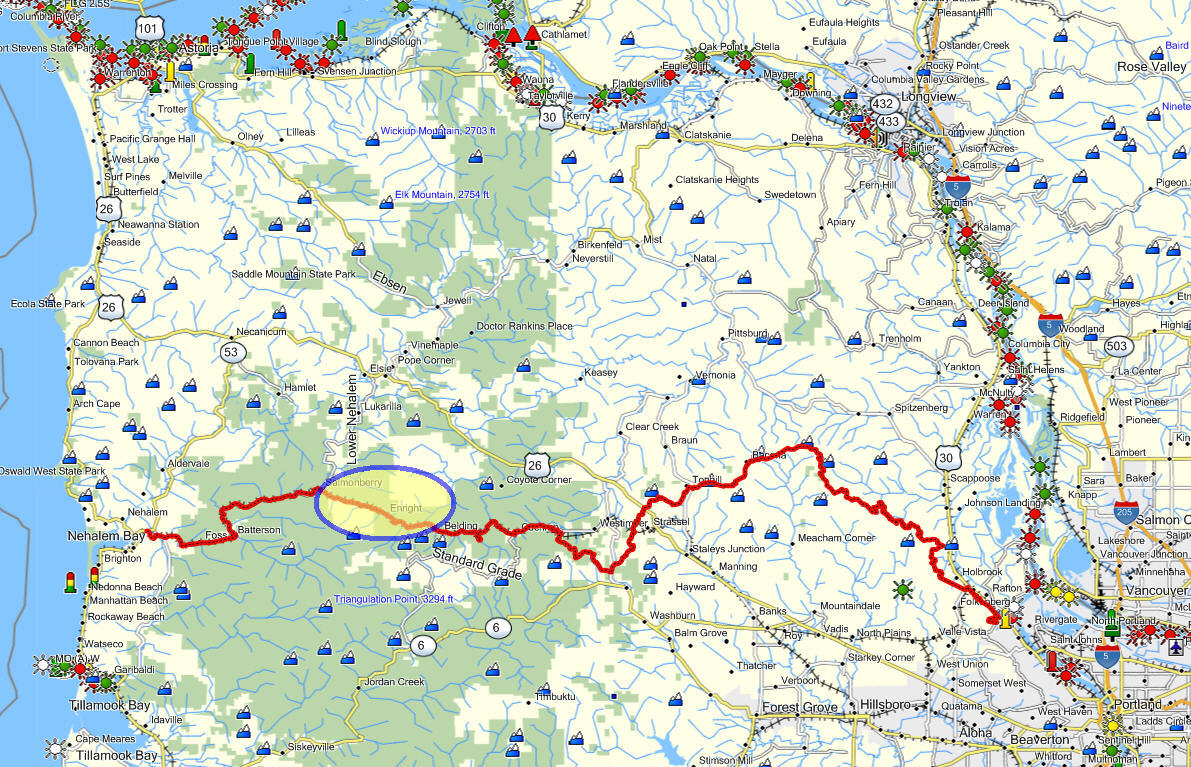

North Fork of the Salmonberry Trail

North Fork of the Salmonberry Trail