When I’m climbing in the hills above the Columbia River I often stop to gaze down into the valley and try to imagine what it looked like before contact with the European cultures.  Most people’s preconception of what the lower Columbia river basin looked like when the first people ruled the roost is of a vast forested area dotted here and there with small bands of Indians that wandered about sporadically in pursuit of game, salmon, wild onions punctuated with an occasional raid on their neighbors.

Most people’s preconception of what the lower Columbia river basin looked like when the first people ruled the roost is of a vast forested area dotted here and there with small bands of Indians that wandered about sporadically in pursuit of game, salmon, wild onions punctuated with an occasional raid on their neighbors.

But in fact, had we looked down upon the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia River 200 years ago we would have seen a landscape very different from today’s crisply maintained waterways.

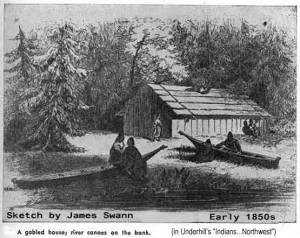

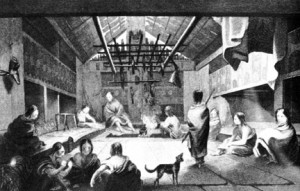

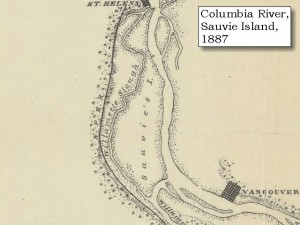

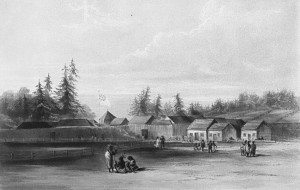

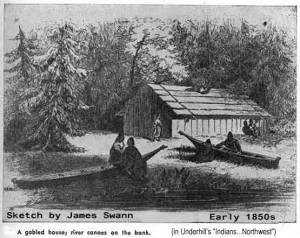

Imagine it’s 1750 and we’re that we’re standing atop the Tualatin Ridge gazing northwards just as the sun crests the cascades mountain to the East. With light flooding across the Willamette Valley, we would have had to shield our eyes to peer down to see Sauvie Island and the confluence of the Columbia River with Willamette River. In this early light the Columbia River would have appeared like so many pewter ribbons threading their way through a maze of sandbars, side channels and islands, splitting and regrouping as it surged northward. And along the river’s swampy boundaries, we would have spotted twisting columns of smoke ascending lazily from scores of plank houses clustered densely on the banks of the big muddy river. Upon closer count, no less than 16 Multnomah and Clackamas Indian villages would have been visible immediately below our lofty observer.

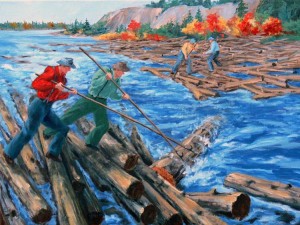

To the modern observer the lack of a clear and continuous shorelines would have been immediately apparent. Instead of a clearly defined river, the many channels and tributaries extended well beyond the main channel and formed a vast bayou of intertwined islands, innumerable streams, stagnant inlets, land-locked ponds, tidal lakes, marshes and flooded woodlands. During the spring floods much of the area would be submerged and the main stem of the muddy river would be clogged with huge debris piles, floating logs and rafts of jumbled flotsam.

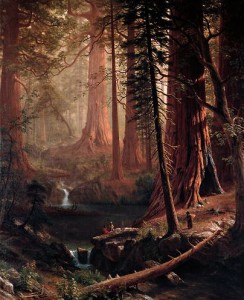

Visually the most arresting feature would have been the ubiquitous stands of timber that bordered every waterway. All along the major channels the shores would have been crowded with thick riparian belts of ash, black cottonwood, willows, big leaf maples, Douglas Fir and Western Red Cedar that grew in rich profusion. Only in the vicinity of the villages, where th e Indians had harvested wood for firewood did the trees recede. Occasionally the careful observer might also spot portions of the shoreline that had been intentionally burned but had since regrown with willows. This selective clearing and subsequent targeted propagation was intentional to ensure a handy supply of willow wood with which to make infant cradles, headgear and household utensils.

e Indians had harvested wood for firewood did the trees recede. Occasionally the careful observer might also spot portions of the shoreline that had been intentionally burned but had since regrown with willows. This selective clearing and subsequent targeted propagation was intentional to ensure a handy supply of willow wood with which to make infant cradles, headgear and household utensils.

Indeed, the entire landscape would have been profoundly affected by the Indians practice of burning the forests and fields throughout the region. Here our observation would have to rely less on our visual acuity, but more upon our understanding of the natural and human proce sses at work in the landscape. So a knowledgeable Indian standing beside us might have explained that the sharp transition from tall stands of timber alongside the waterways to the grassy clearings interspersed with islands of white oak was no natural accident, but was instead the direct result of the Indians’ fire induced land management.

sses at work in the landscape. So a knowledgeable Indian standing beside us might have explained that the sharp transition from tall stands of timber alongside the waterways to the grassy clearings interspersed with islands of white oak was no natural accident, but was instead the direct result of the Indians’ fire induced land management.

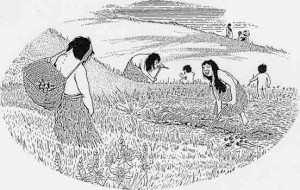

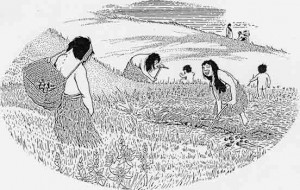

In the late fall after the annual burning, these cleared areas would have clearly shown the effects of the fire induced thinning. Shielded by their thick bark, the oaks withstood the seasonal scorching and rewarded both humans and deer with their bounty of acorns. In between the copses of oaks the charred clearings soon regenerated into a lush crop of native grasses, including Blue Ryegrass, Idaho bent grass, California Oatgrass, Needlegrass and Tarweed. To the unfamiliar eye, this diverse ground cover held no significance, but to our native observer these grasses would have represented yet another important source of food. Tarweed, for example, is a sunflower-like plant that grew throughout the region. The fire would scorch this tall plant removing the sticky tar substance and leaving the husk full of seeds ready to be harvested. Burning away the ground cover, would also have facilitated the harvesting of the grass seeds, as well as exposing a delicious bounty of roasted crickets!

Beyond this transitional growth the landscape opened up into wide savannahs and luxuriant grasslands that stretched south all the way to the end of the Willamette Valley and up into the forested foothills on the valley’s eastern and western flanks. Only where the valleys rose up the flanks of the foothills did the Douglas Fir, Ponderosa Pine, Hemlocks and Big Leaf Maples reasserted their arboreal dominance. And even there the Indians were fond of burning swathes of cleared land on the western facing slopes to help the propagation of huckleberry patches. Near the summits, hunter were wont to fire the ridge lines to provide corridors that would attract the deer and elk to the new growth, and make hunting easier.

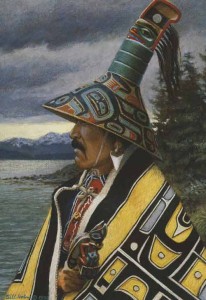

Most of the human habitation was concentrated along the lower Columbia extending from the Sandy River down to the Cowlitz river, a region sometimes referred to as the “Wapato Valley”. This basically encompasses what is now the Portland/Vancouver metropolitan areas, on down to Kelso, WA. It is estimated that this region was home to more than 14,000 people, and that prior to the first huge epidemics in the 1700’s, the population may have been as high as 30,000 to 40,000 people. These population densities in the early 1800’s equate to more than 1 person per square mile.

But before  the devastating epidemics of the 1700, the population density rises to an astounding 3.1 people per square mile – a remarkable population concentration give the fact that most of the habitation was located along the banks of the river and that this was a hunter-gather society that did not cultivate plants in any organized fashion. How was it possible to sustain that many people without an significant agricultural efforts. The answer lies in the remarkable fecundity of the Columbia River basin. It was home to elk, bear, dear, beaver, ducks, geese, sturgeon, salmon, smelt, wapato bulbs, camas bulbs, a profusion of berries including salal and huckleberries. Historians think that the Columbia River may have been the richest river in the world disgorging between 11 and 16 million salmon per year. And the Indians are estimated to have caught more than one fish in three!

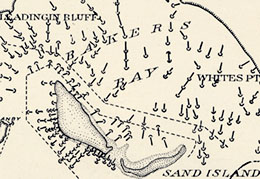

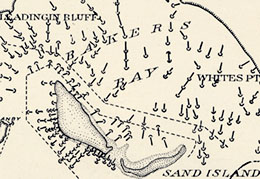

the devastating epidemics of the 1700, the population density rises to an astounding 3.1 people per square mile – a remarkable population concentration give the fact that most of the habitation was located along the banks of the river and that this was a hunter-gather society that did not cultivate plants in any organized fashion. How was it possible to sustain that many people without an significant agricultural efforts. The answer lies in the remarkable fecundity of the Columbia River basin. It was home to elk, bear, dear, beaver, ducks, geese, sturgeon, salmon, smelt, wapato bulbs, camas bulbs, a profusion of berries including salal and huckleberries. Historians think that the Columbia River may have been the richest river in the world disgorging between 11 and 16 million salmon per year. And the Indians are estimated to have caught more than one fish in three! This early map below shows the absolute profusion of fish weirs, and fish traps on the lower Columbia River.

This early map below shows the absolute profusion of fish weirs, and fish traps on the lower Columbia River.

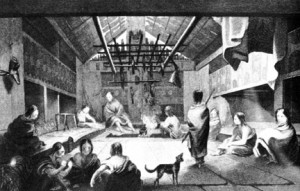

Returning to our vantage point looking down towards the lower reaches of the Willamette River, we can easily see wood smoke rising from numerous plank houses clustered along the river that comprise several villages of the Multnomah Indians. Dogs wander in and out of the lodges, unheedful that their final destination will be in the Indian stew pot. As it lightens there’s activity stirring around the villages with women emerging from the small entrance at the front of the plank house. They’re probably going out to check the overnight catches in the many fish weirs constructed all along the river’s shallows. But mainly everyone seems to be  getting ready for the spring runs of salmon. Back from the river shore, we can spot a group of women carefully gathering plants growing on the sandy soil. Judging from the delicacy of how they handle the plants we can surmise that they must be standing in the middle of a nettle patch! Despite its unpleasant reputation the Indians considered this the best plant from which to make strong and silky lines which were ideal for fishing – and were thus in high demand as the seine nets were being repaired for the spring salmon run.

getting ready for the spring runs of salmon. Back from the river shore, we can spot a group of women carefully gathering plants growing on the sandy soil. Judging from the delicacy of how they handle the plants we can surmise that they must be standing in the middle of a nettle patch! Despite its unpleasant reputation the Indians considered this the best plant from which to make strong and silky lines which were ideal for fishing – and were thus in high demand as the seine nets were being repaired for the spring salmon run.

On the north shore we spot another group of women walking into the interior of Sauvie Island. They’re shouldering a small canoe on their shoulders as they thread their way through the vine maple thickets that surround the waters of Sturgeon lake. From our lofty vantage point we can just barely see them wading out into the water until they’re nearly waist deep in the muddy lake. The women pause, and pensively shuffle around in the waist deep water feeling the bottom of the pond with their toes. Presently one of the women slips her toes around a wapato root and with a slight pull dislodges it from the bottom of the pond. It quickly pops up to the surface whereupon she tosses the bulbous root into the little canoe that is floating alongside her. Clustered around her the other women are also retrieving the dislodged roots and depositing them in their floating wheelbarrows.

On the north shore we spot another group of women walking into the interior of Sauvie Island. They’re shouldering a small canoe on their shoulders as they thread their way through the vine maple thickets that surround the waters of Sturgeon lake. From our lofty vantage point we can just barely see them wading out into the water until they’re nearly waist deep in the muddy lake. The women pause, and pensively shuffle around in the waist deep water feeling the bottom of the pond with their toes. Presently one of the women slips her toes around a wapato root and with a slight pull dislodges it from the bottom of the pond. It quickly pops up to the surface whereupon she tosses the bulbous root into the little canoe that is floating alongside her. Clustered around her the other women are also retrieving the dislodged roots and depositing them in their floating wheelbarrows.

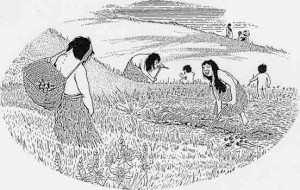

Later in the year, we might have seen the Indian women wearing long conical baskets fanning out into the grasslands to fire the grasses. Systematically the Indians would fire all the grasslands that extended down from the forested hillsides – all the way to the riparian strips that clustered along the waters edge. It was hot and smoky work and it reduced visibility to just a few yards. Later the women would return to harvest the newly exposed seeds into their gathering baskets. At times the men would organize the burning strategies to drive the game into the reach of the waiting hunters.

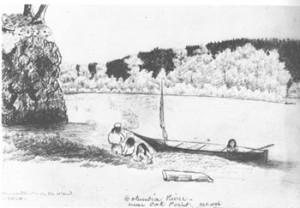

Back at the village, the men are now emerging from the plank houses. Several of them are leaning on their typical chinookan paddles so recognizable because of the triangular scoop and the straight-edged end. Others are collecting their bows and arrows and stringing new bow strings. Aside from this gear most of them are entirely naked – as was the custom for men through most of the warmer months in the year. Apparently, they are planning to hunt the huge Roosevelt Ek that frequented the wooded slopes – probably to smoke and then sell at the annual “rendezvous” above the Cellilo falls.

Eventually, they drag one of the canoes down to the water and after a boisterous send-off  we observe them paddling down a small channel that separates the island from the western shore. About a mile down what we now call the “Multnomah Channel” they disembark on the western shore. The hunters are barely visible as they wade through fields of luxuriant grasses. Dotted throughout the landscape White oaks provide shade and cover. Eventually the forest begins to take shape around them as they ascend into the foothills of the Tualatin Range.

we observe them paddling down a small channel that separates the island from the western shore. About a mile down what we now call the “Multnomah Channel” they disembark on the western shore. The hunters are barely visible as they wade through fields of luxuriant grasses. Dotted throughout the landscape White oaks provide shade and cover. Eventually the forest begins to take shape around them as they ascend into the foothills of the Tualatin Range.

Had we the eagle eyes to recognize the trees into which the hunters were climbing, we would see that it too differed markedly from today’s forests. Of course, the slopes were covered in majestic old growth Douglas Fir trees, mixed with stands of Grand Fir and Ponderosa Pines. And the ground was uniformly covered in the Oregon grape and salal that is still ubiquitous today. But there the similarity would end, because the Western Hemlock that grows on these slopes today would have been largely absent. Even the western cedar trees would mainly be found congregating further up the Willamette, near present-day Portland.

But where are these hunters going? Though we cannot see from our lofty vantage point they are traveling one of the oldest routes in the region. This trail had for years been the main route for crossing the hills and from there gaining access to the savannahs that provide a clear passage all the way south through the lands of the Calapooyans to the foothills of the Siskyou mountains.

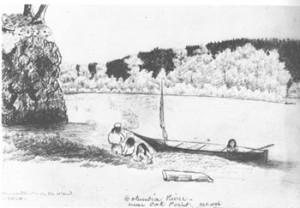

Even the shoreline was unrecognizable to modern eyes.  Gone were the well defined river banks and instead we see endless streams and inlets piercing the river banks and shallow bayou’s along the river’s edge where fish swam into the myriad inlets, streams and shallow ponds. And there we would see a the handiwork of the Indian fish trappers with their wooden weirs, basket traps and wooden fishing platforms. The eastern shore of Sauvie Island had the recognizable beaches, but all along the length of the island small streams breached the shoreline feeding shallow channels that penetrated deep into the interior feeding into Sturgeon lake.

Gone were the well defined river banks and instead we see endless streams and inlets piercing the river banks and shallow bayou’s along the river’s edge where fish swam into the myriad inlets, streams and shallow ponds. And there we would see a the handiwork of the Indian fish trappers with their wooden weirs, basket traps and wooden fishing platforms. The eastern shore of Sauvie Island had the recognizable beaches, but all along the length of the island small streams breached the shoreline feeding shallow channels that penetrated deep into the interior feeding into Sturgeon lake.

And everywhere, we can see the smoke rising from the hundreds of plank houses scattered across the landscape, and from these villages we can spot footpaths leading up into the berry gathering grou nds on the western facing slopes that caught the warm afternoon sun. Trails also ascended both the Tualatin Hills and the foothills of the Cascades on the eastern shore of the river. These trails climbed to the crests, where hunters torched the enormous stands of virgin timber to create artificial clearings. It was in these riparian areas that elk and the deer would emerge from the gloom of the forest to enjoy the young vegetation that grew there. And it was there the hunters would return to hunt.

nds on the western facing slopes that caught the warm afternoon sun. Trails also ascended both the Tualatin Hills and the foothills of the Cascades on the eastern shore of the river. These trails climbed to the crests, where hunters torched the enormous stands of virgin timber to create artificial clearings. It was in these riparian areas that elk and the deer would emerge from the gloom of the forest to enjoy the young vegetation that grew there. And it was there the hunters would return to hunt.

But in the meantime, the hills burned and smoke filled the sky. Along the entire inland valley that stretched from the headwaters of the Willamette River to the Puget Sound a pall of smoke would hang heavy from July into late September. It was so thick that Indians didn’t dare navigate beyond the immediate  shoreline in the Puget Sound, lest they be lost interminably in the thick smoke that hung over the region.

shoreline in the Puget Sound, lest they be lost interminably in the thick smoke that hung over the region.

So far our observers have been looking northwards towards the confluence of the Willamette and the Columbia – an area now dominated by shipping facilities in the industrial Rivergate area and farming on Sauvie Island southern edge.

The area of downtown Portland, teeming with human activity today, was virtually deserted in those distant days. The difference lay in the way the Indians used the land. For them prime real estate was was defined by the proximity of migrating salmon or immediate and visual access to transiting canoe traffic on the main stem of the Columbia river. SW Portland had none of these qualities, and shaded from the warm afternoon sun by the hills it lacked even decent huckleberry patches. The area was dominated by a large pasture that occasionally hosted temporary Indian gatherings, but it was not a well frequented area. The streams that descended from the steep slopes hosted native populations of trout, but in the native food chain trout were a trivial resource that could not sustain any village for very long. It was across the river at the mouth of the Clackamas that the Indian congregated to collect their harvest of salmon. Further up the river the falls did provide good reason for the Indians to congregate. It was there that the Indians would gather in early summer to wade waist deep into the vast pools of eels gathering at the base of Willamette Falls. Reaching into the water they would grasp armfuls of the writhing eels and toss them onto the shore where children competed to gather up as many as they could before the eagles, ospreys and giant Columbia River condors snatched the wriggling fish from the rocks.

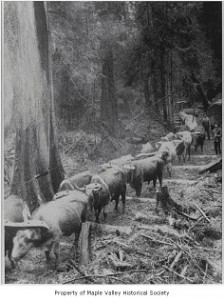

The landscape of pre-contact was no more “natural” than it is today, but the patterns differed markedly. All activity radiated from the river’s edge which was both the major transportation arterial as well as the greatest source of food and commerce. The early settlers with their land-based paradigm of wagons and cattle were blind to the “organization” of the natural resources that their predecessors ahd bequeathed them.

We leave our observers now, as the warming day floods light over this riverine landscape. With the help of our native host, we marvel at the industriousness of the Indian fishermen whose ubiquituous weirs, fish wheels and seining pervaded the myriad channels and bayous of the river. Everywhere canoes were plying the great watery highway fishing and trading as part of the complex system that enabled the survival of such an intense concentration of people in such a small area.

Just visible under the clouds our erstwhile observer would have been able to spot the snow-dusted hills that mark the lower slopes of Cascade Mountains. No doubt our long-ago observer would  have taken comfort from the presence of the great “sentinel” mountains hidden in the clouds. Like great soldiers, the majestic peaks of Tahoma (Mt. Rainier), Loo-Wit (St. Helens), Klickitat (Mt. Adams), and Wy East (Mt. Hood), had stood guard over this richly endowed region since the Indians’ arrival nearly 10 thousand years ago. Unfortunately, the next two centuries would prove the demise of their heretofore sustainable lifestyle. Will our approach prove more or less sustainable – it remains to be seen by the next observer.

have taken comfort from the presence of the great “sentinel” mountains hidden in the clouds. Like great soldiers, the majestic peaks of Tahoma (Mt. Rainier), Loo-Wit (St. Helens), Klickitat (Mt. Adams), and Wy East (Mt. Hood), had stood guard over this richly endowed region since the Indians’ arrival nearly 10 thousand years ago. Unfortunately, the next two centuries would prove the demise of their heretofore sustainable lifestyle. Will our approach prove more or less sustainable – it remains to be seen by the next observer.

Without a doubt the overwhelming fecundity of the region and the strategic importance of the Columbia River influenced both native and subsequent immigrant economies. The Chinook were prodigious traders swapping goods from Alaska to California and from the mouth of the Columbia to the western plains of Wyoming and Nebraska. The Hudson Bay quickly learned this same lesson when they quickly turned to exporting fish and timber within 5 years of establishing the fort in Vancouver. It wasn’t until the first wave of “overlanders” arrived in 1843 that the river-based paradigm was overturned by an army of cows and wagons and the subsequent agricultural development that ensued. And from that point onwards the land began to change in ways that would erase the prior organization of nature that had served the Indians for over 10,000 years. In response to an international market system, the civilization of Oregon would obliterate the legendary fecundity of the Columbia River Valley – reversing ten millennia of communal stewardship in less than 150 years of private exploitation.

Upon reading my materials and observations on the Oregon Coast Range the question frequently arises as to what distinguishes my perspectives on this landscape from that of others. I can’t say I really thought much about this while I was busily wearing out my hiking boots. But perhaps my thirst for exploring our trackless wilderness is a bit out of the ordinary, or else I would have encountered more like-minded spirits.

Upon reading my materials and observations on the Oregon Coast Range the question frequently arises as to what distinguishes my perspectives on this landscape from that of others. I can’t say I really thought much about this while I was busily wearing out my hiking boots. But perhaps my thirst for exploring our trackless wilderness is a bit out of the ordinary, or else I would have encountered more like-minded spirits. Bavarian Alps surrounded by precipitous peaks. In the winter the mountains blocked the sun for much of the day, and the avalanches roared into the valley whenever we had a heavy snowfall. Mountains loomed large in my youth, as the home of mysterious folk-lore spirits, as an inviting network of precarious cliff clinging goat trails, an unending inventory of musty caves to be explored, a trove of abandoned World War II arms caches and a playground of lofty eyries

Bavarian Alps surrounded by precipitous peaks. In the winter the mountains blocked the sun for much of the day, and the avalanches roared into the valley whenever we had a heavy snowfall. Mountains loomed large in my youth, as the home of mysterious folk-lore spirits, as an inviting network of precarious cliff clinging goat trails, an unending inventory of musty caves to be explored, a trove of abandoned World War II arms caches and a playground of lofty eyries  from which to view the world beyond my valley. Constantly warned off these perilous slopes by my cautious parents, I was not to be deterred from crawling up the most precarious faces and poking into every crevasse to tease out the myriad secrets these crags had to offer. There was something in me that reveled in the experience of being beyond the orderly reach of civilization. In my passionate teen years I was given to reciting Lord Byron’s romantic verse from the top of mountain peaks. Somehow the thrill of the claiming for myself these secret places deep in the forest or high up on the forbidden rock faces was a romantic urge that never quite left me…

from which to view the world beyond my valley. Constantly warned off these perilous slopes by my cautious parents, I was not to be deterred from crawling up the most precarious faces and poking into every crevasse to tease out the myriad secrets these crags had to offer. There was something in me that reveled in the experience of being beyond the orderly reach of civilization. In my passionate teen years I was given to reciting Lord Byron’s romantic verse from the top of mountain peaks. Somehow the thrill of the claiming for myself these secret places deep in the forest or high up on the forbidden rock faces was a romantic urge that never quite left me… reverence my friends and relatives from America felt in visiting the local castle. But when I came to Oregon and beheld for the first time the vast and empty spaces of eastern Oregon, I felt a similar awe. And every time I walk deep in the forests, I am reminded of how little time has past since this land was completely primeval. Where European civilization emerged from the woods and marshes well over 2000 years ago, here in the Pacific Northwest man has only just emerged from the domination of our colossal rain forests. Standing deep in the Oregon’s coastal forests, amongst the noble Western Cedars, beneath the huge Sitka Spruce giants and the ubiquitous Douglas fir I feel as if I am transported back in time to a time when men’s mark on nature was still fresh. These are literally the densest forests on earth, and their dark loamy environment fed by nutrient rich high latitude ocean weather simply reeks with life. In the dark and close confines of Oregon’s coastal forest life as we know it ceases and the rules are reversed. Hundreds of people have been lost in these forests, never to reappear. Planes go down into the forest canopy and it closes around the wreckage forever hiding the remains. Even DB Cooper and all his loot was swallowed alive. Apply your sensible Boy Scout wisdom about following water to safety and it will most assuredly lead you to your doom in this primeval jungle. Civilization simply does not penetrate into these remote ravines. When I am in the deep forests and utterly alone, it’s exhilarating to think back to a time thousands of years ago when we had not yet mastered our environment and were still inexorably subject to the whims of nature.

reverence my friends and relatives from America felt in visiting the local castle. But when I came to Oregon and beheld for the first time the vast and empty spaces of eastern Oregon, I felt a similar awe. And every time I walk deep in the forests, I am reminded of how little time has past since this land was completely primeval. Where European civilization emerged from the woods and marshes well over 2000 years ago, here in the Pacific Northwest man has only just emerged from the domination of our colossal rain forests. Standing deep in the Oregon’s coastal forests, amongst the noble Western Cedars, beneath the huge Sitka Spruce giants and the ubiquitous Douglas fir I feel as if I am transported back in time to a time when men’s mark on nature was still fresh. These are literally the densest forests on earth, and their dark loamy environment fed by nutrient rich high latitude ocean weather simply reeks with life. In the dark and close confines of Oregon’s coastal forest life as we know it ceases and the rules are reversed. Hundreds of people have been lost in these forests, never to reappear. Planes go down into the forest canopy and it closes around the wreckage forever hiding the remains. Even DB Cooper and all his loot was swallowed alive. Apply your sensible Boy Scout wisdom about following water to safety and it will most assuredly lead you to your doom in this primeval jungle. Civilization simply does not penetrate into these remote ravines. When I am in the deep forests and utterly alone, it’s exhilarating to think back to a time thousands of years ago when we had not yet mastered our environment and were still inexorably subject to the whims of nature.

the chanterelles, and the border patrol to learn more about the movement of our herds. Unlike the United States there was a symbiotic relationship between all these parties and we learned from each other even as we crossed paths high up in the range. Since logging was done selectively the impact to the wildlife was minimal, our control of the game population protected the farmers’ crops, and our concealed mountain trails served the mushroom scavengers and foresters to climb the steep slopes. Thus I came to consider the forest from many angles and to appreciate the interwoven network that sustained this delicate ecosystem.

the chanterelles, and the border patrol to learn more about the movement of our herds. Unlike the United States there was a symbiotic relationship between all these parties and we learned from each other even as we crossed paths high up in the range. Since logging was done selectively the impact to the wildlife was minimal, our control of the game population protected the farmers’ crops, and our concealed mountain trails served the mushroom scavengers and foresters to climb the steep slopes. Thus I came to consider the forest from many angles and to appreciate the interwoven network that sustained this delicate ecosystem. on destruction of this ant pile. It seems that the family bible, handed down from generation to generation, had reported faithfully on this insect colony that had sprung up alongside the new farm when it was founded in 1060 AD!

on destruction of this ant pile. It seems that the family bible, handed down from generation to generation, had reported faithfully on this insect colony that had sprung up alongside the new farm when it was founded in 1060 AD! nitely complex life and death dance that sustains fish, fowl, fur and flower. While you are knee deep in the crunchy spring snow, can you hear the distant cacophony of human destruction, or sense the microcosmic drama of 16,000 invertebrates living beneath your every footstep? This is a world that runs itself, no batteries needed. It is both off the grid, and it is the only grid. Like a blind man groping around the edges of an unfamiliar object, I come here to feel the limits of our influence and to understand the real shape of things.

nitely complex life and death dance that sustains fish, fowl, fur and flower. While you are knee deep in the crunchy spring snow, can you hear the distant cacophony of human destruction, or sense the microcosmic drama of 16,000 invertebrates living beneath your every footstep? This is a world that runs itself, no batteries needed. It is both off the grid, and it is the only grid. Like a blind man groping around the edges of an unfamiliar object, I come here to feel the limits of our influence and to understand the real shape of things.